Nearly every week, a mystery is solved or some interesting twig (or nut) appears somewhere on the family tree. Here is a little news of recent findings.

Like most weeks, my work on the McCall book has led me to some fascinating stories. In this post, I’ll introduce you to one McCall descendant who was maimed and another who was murdered—just a glimpse into the many tales within the family tree.

Maimed

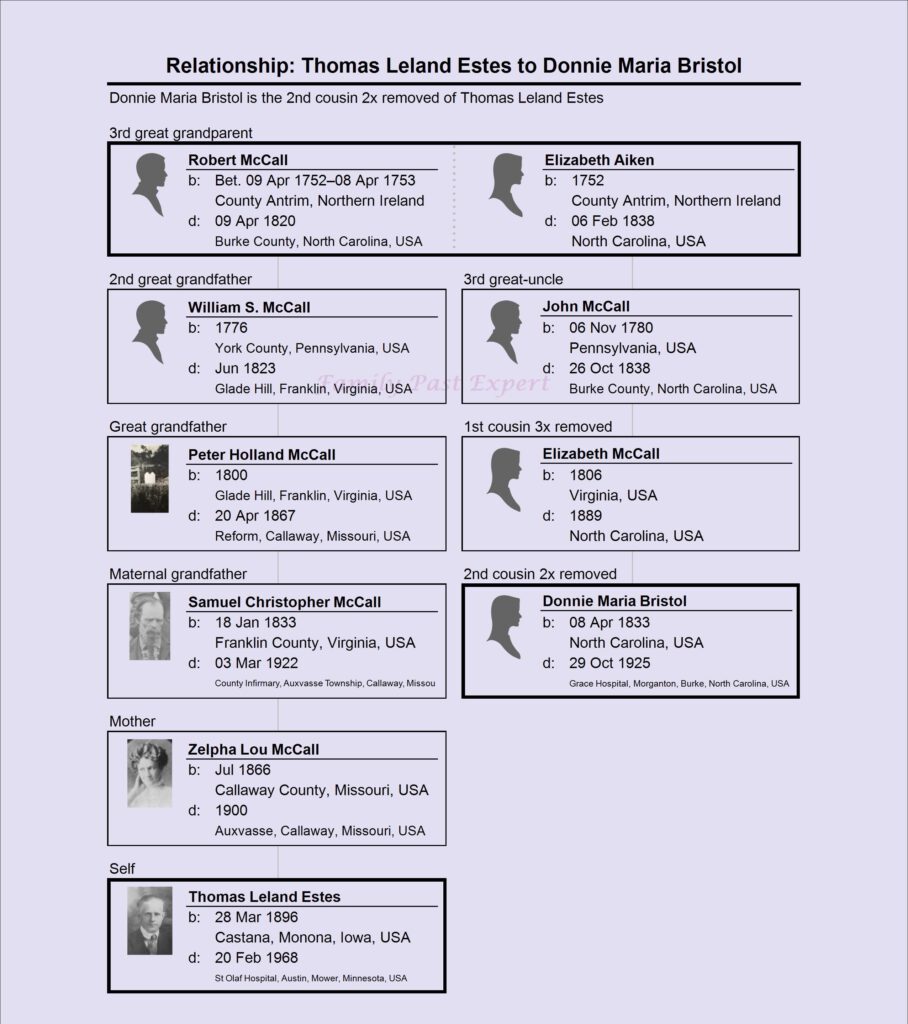

Donnie Maria Bristol Sudderth’s life was marked by strength and resilience. Born in 1833, she raised a large family, endured the hardships of the Civil War, and suffered a devastating accident that would have halted most lives. Yet, even after losing both arms, Donnie adapted to her circumstances, raised her children, and inspired admiration within her community. Her story offers a vivid look at one remarkable woman in our McCall family tree.

Donnie Maria Bristol was born on 08 April 1833, in North Carolina, the third of twelve children born to Benedict Bristol and Elizabeth McCall.

At 23, she married William Sydney Sudderth on 11 November 1856, in Burke, North Carolina. Over the following two decades, they welcomed nine children, managed their plantation, and endured the Civil War. William even garnered attention for his success with his hogs.1 Their plantation also produced sugar cane, a crop that would eventually play a tragic role in Donnie’s life.

Around 1874 or 1875, when she was about 44, Donnie suffered a life-altering accident. While instructing a worker on using the sugar cane mill, both of her arms were caught in the machinery and torn off at the elbows. Remarkably, she survived and found ways to adapt to her disability. Donnie continued raising her children, including an infant born a couple years after the accident. Family stories suggest that while holding her youngest, she may have accidentally dropped the child into the fireplace, into the fire and onto the stone hearth; this child grew up with a mental disability.

William passed away in 1885, around ten years after Donnie’s accident, leaving her to carry on without him. Donnie lived another four decades, becoming known for her resilience. Upon her death at age 92, the News and Observer paid tribute to her, noting, “About fifty years ago, while showing a farm hand how to operate a can [sic] mill, she lost both arms above the elbow, but in spite of this affliction she had gone through life bravely and was considered in many ways one of the most remarkable women in Morganton.”2

As I encountered Donnie in my research, it was also nice to [virtually] meet one of her descendants, a sixth cousin to me, who has graciously given permission to use Donnie’s photo in my upcoming McCall book.3

Murdered

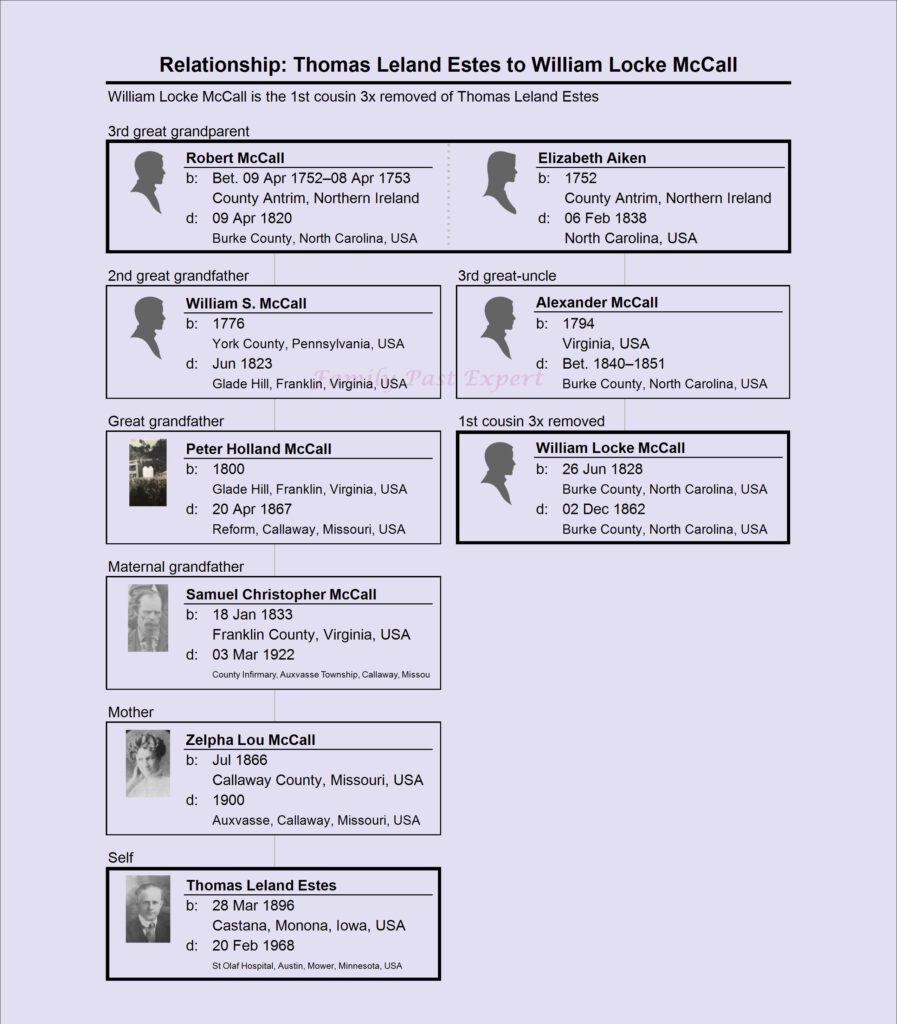

Unlike his first cousin, one time removed Donnie, William Locke McCall did not get to live a long life. He was born 26 Jun 1828 in Burke County, North Carolina. He married, started his family, farmed, and did blacksmith work.

On a December night in 1862, William McCall was out with his friends. They were playing cards and drinking after a day with their military unit. On the walk home from the party, things took a turn and McCall ended up dead.

The murderer was John Twiggs. McCall and Twiggs were neighbors in Burke County, North Carolina, and ran in the same circle of friends. Both were in their 30s and married with children.

McCall and Twiggs were both in the Home Guard in Burke County but had not yet been conscripted and sent off to fight for the Confederacy in the Civil War. In late 1862, there may have already been grumblings about the new laws the Confederate government was planning to implement in 1863 that would require 10% of key farm products such as corn, wheat, livestock, and cotton to be contributed to that government. With most of the young men of the county already at war and the rules regularly changing, people were no doubt on edge.

Some accounts say that the men were friendly, others that there was bad blood between the two because McCall had testified against Twiggs in a court case a few years earlier.

All accounts say that both men had been drinking. Drinking on a Monday night. Located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, the weather was probably damp and cool. It may have been around 50 degrees while the men were drilling, but the night would have been cooler, probably nearing freezing.

They had been with others playing cards and drinking. At some point, a group including McCall and Twiggs, along with Austin Smith and William Spinks, decided it was time to leave and took off towards home. The group separated to cross a ditch and while Twiggs and McCall were alone, Twiggs stabbed McCall. The rest of the group caught up and arrested Twiggs.

Twiggs ran. McCall died the next morning.

Twiggs was arrested and brought to trial in 1863.

He was indicted.

“John Twiggs late of the County of Burke aforesaid laborer not having the fear of God before his eyes, but being moved and seduced by the instigation of the devil on the first day of December in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty two, with force and arms at and in the County aforesaid, in and upon one William McCall in the peace of God and the State then and there being feloniously, willfully and of his malice aforethought did make an assault and that the said John Twiggs, with a certain knife of the value of sixpence which he the said John Twiggs, in his right hand then and there had and held him, the said William McCall in and upon the left side a little to the back part thereof of him the said William McCall then and there feloniously wilfully [sic] and of his malice aforethought, did strike thrust and stab McCall giving to the said William McCall then and there, with the knife aforesaid, in and upon the left side a little to the back part thereof, of him the said William McCall, one mortal wound of the breadth of three inches and the depth of six inches of which said mortal wound the said William McCall then and there instantly died; and so the Jurors aforesaid upon their oath aforesaid do say that the said John Twiggs, the said William McCall in manner and form aforesaid feloniously, wilfully [sic] and of his malice aforethought did kill and murder against the peace and dignity of the state. ”

Twiggs pleaded not guilty. He asked for a change of venue. Among the jurors was W.C. Corpening who was also one of the guys who put up bond when William McCall’s estate was inventoried and sold – William’s wife’s maiden name was Corpening.4 The clerk of the court was W.S. Suddereth, husband of Donnie whose story we just told. Donnie’s mother and William were first cousins. Twiggs was wise to realize that he probably would not get an impartial jury or fair trial in Burke County.

The trial was moved to nearby Rutherford County, North Carolina.

Twiggs was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. He was granted an appeal and remanded to the Burke County jail.

“Wherein came the following Jury, to wit, Wm Many, A M Sing, Rankin Helifield, Wm Davis, White Williams, John Smith, William Hays, Philip Hesen, John McDaniel, Miss McDaniel, E. D. Hawkins, W Whiteside, who being drawn, sworn and charged find the defendant guilty of the felony and murder in manner form as charged in the bill of indictment. The prisoner is remanded.

Judgement of the Court, that the defendant be taken to the County of Burke, from whence he came and kept in close confinement until Friday the 2nd day of Jany 1863, when he be taken to the place of public execution & then hanged by the neck, until he be dead and the Sheriff of Burke County is to carry this sentence into effect. Rule upon the State to show cause why a new trial shall not be granted. While discharged, Appeal prayed for which is granted by the Court, it being made to appear that the prisoner is unable to give security. Ordered that the Sheriff of this County safely deliver the prisoner to the Sheriff of Burke County to be kept in the jail of Burke County.”

In a biography, written by his family, a guess was made that Twiggs left North Carolina in November 1863 to join up with Union forces who had established control over eastern Tennessee. However, the real reason for leaving North Carolina was probably that when escaping from jail, abandoning your Confederate comrades and joining up with Federal Troops was a good way to hide and escape being hung.

According to his family’s research, on 09 November 1863, Twiggs enlisted as a private in Company G of the 13th Regiment of Tennessee. That unit was mustered into the Union Army on 13 April 1864 at Nashville and saw action in Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina. In the fall of 1864, Twiggs’ horse stumbled, and he fell. He sustained permanent damage to his left side.5

Despite his injury, Twiggs survived the war, and his family joined him in Tennessee. He lived there for the next twenty years, remarrying in 1879 after his first wife passed away. He raised a family and was considered a good citizen.

Eventually, his past caught up with him and in 1883, Twiggs was caught and returned to North Carolina to face his past murder charge.

His story was covered in newspapers across the state. Some of the news accounts were more accurate than others. The Carolina Mountaineer reported in detail, but they got many facts wrong such as the date of the murder.

“a Tennessean came to Solicitor Adams and informed him that Twiggs was living in Carter county Tennessee and could be captured. Nothing was done with the case, however, until a few months ago, when Mr. Perry, formerly town Marshal of Morganton, was employed by the State to go to Mitchell and other border counties in North Carolina and Tennessee to assist in breaking up a band of outlaws that had taken refuge there and were committing depredations. Among others whom Perry was instructed to arrest was this man John Twiggs … Perry made the arrest and Twiggs has been brought back to North Carolina and lodged in the same jail in Rutherfordton, from which he escaped more than a score of years ago.”6

There are no other accounts of Twiggs’ capture, so this may be true. But it was the Burke County jail from which Twiggs had escaped, not the jail in Rutherfordton

The witness and defendant testimonies sometimes conflicted. For example, the killing was originally reported to have taken place on 01 December 1862, yet the witness, Austin Smith, remembered it happening in October. The killing had happened decades earlier and one of the men there that night was no longer alive. Memories may have been fading. Details may have been added since the original trial.

Austin Smith testified that in October 1862, he was returning to his house in Burke County, having been at work up on John ‘s River in that County, and passed the house of one Milton Kincaid, near whose still house, he said the prisoner, the deceased and one Spinks and another playing cards. Upon being hailed witness stopped and after the game was ended, went with the party to Kincaids house, when said Spinks, since deceased, bought a quart of liquor, and the crowd drank round when Spinks filled a pint bottle from the quart, and the party started off. The Prisoner as they started said to deceased “I’ll take your gun” and picked up both his own and deceased’s gun, the deceased remarking in answer to Prisoners remark, “Well take it, I don’t care who carries my gun.” Deceased was under the influence of liquor, “tight” as expressed by witness, but could “go.”

The party, who were all going in the same direction home marched in single file, witness in the lead, deceased behind him and Prisoner behind him and Spinks last.

After proceeding in this order about a half mile, they came to a little ditch where there were many briars on both sides, with Cornstalks and thick briars on the other side, when witness, ( who was familiar with this route having passed over it several times, both by day and night going to and returning from his work) said he would where get over in a more open place, where there were no briars, and turning to the right, did cross the ditch further up, the others, as witness supposed going straight on by the path; after going 6 or 8 Steps beyond the ditch, deceased called to witness to come back , that “John Twiggs had killed him, had cut him to death.” Witness went to deceased and found him on his all fours in the ditch, told him to “get up” when deceased again said he could not that Twiggs had cut him to death.

Witness then helped Deceased to his feet — and again asked him to go on, when deceased again said he could not, that he was cut. Witness asked “where?” when Deceased pointed to his back, and Witness, by feeling, discovered and felt the warm blood and their looked for Prisoner who was standing 5 or 6 steps off. Witness called to Prisoner to come and help deceased, that he had fallen, that he had fallen and hurt himself, that Prisoner did not come when witness told him if he did not come he was his prisoner. Prisoner then ran and witness pursued and caught him, near an obstructing fence and asked for his knife.

Prisoner produced it and remarked “it is shut.” Witness compelled Prisoner, who hesitated, to return to deceased; asked prisoner what had happened between him and the deceased to make him cut him. Prisoner said nothing same but being enquired of in the same manner the third time answered that “he had wanted to go to the war for sometime, and they could only send him there.”

Witness left Prisoner in the custody of Spinks and returned to Kincaids, got a light and came back, and with the light examined deceased’s wounds. Deceased had two wounds, one on the back of his shoulder blade, as if cut down, the other a cut in the side extending to the backbone. Deceased died the next morning early.

This witness also testified that Deceased and the Prisoner seemed and talked friendly before the homicide.

Twiggs, the accused, took the stand in his own defense. In his earlier trial, he was not allowed to do so. It did not become legal for defendants to testify in their own defense in criminal trials in North Carolina until 1881.7

The Prisoner as a witness in his own behalf testified that he and deceased were members of the Home Guard, and on the day of the homicide, both had been to a muster of the Home Guard, after which he and deceased and others went to Kincaids, got a dram, and went to the still house, when deceased played cards with one Saunders, who won $ 250 from deceased, who then played with Prisoner and for his money back when Prisoner “jumped ” the game.8

That he and deceased and others then went to Kincaids, when Spinks bought a quart of liquor and set it out for the party to drink, and all did drink, that prisoner moved to go on home, when some one said “hold on we will all go.” Spinks filled his tickler and they started from Kincaids, the witness Smith and deceased stopped and had a talk while Prisoner and Spinks passed on and had gone 150 yards when the others called to them to stop. Prisoner wanted to go on but Spinks said “lets wait,” and Prisoner and Spinks did wait till Smith and Deceased came up. Deceased when he came up asked prisoner to carry his gun, saying that he, Deceased was too drunk. Prisoner asked him to give it to some one else but deceased said no, when Prisoner took it, and threw it and his own gun across his arm; that when they got to the ditch Smith and Spinks went round, but Prisoner said “lets go through,” and he and Deceased did go through and that just as they came to the ditch, Prisoner being near the ditch carrying the guns as before described Deceased said “God damn you give me my gun.” Prisoner replied, as he crossed, or after he crossed the ditch, ” I thought you were too drunk to carry your gun.”

Prisoner turned however and handed Deceased his gun, when Deceased struck Prisoner with the gun, inflicting ever against Prisoners efforts to parry the blow, with his hands, a slight wound over the eye.

Deceased came at the Prisoner the second time and struck, but the blow only grazed Prisoners side. Prisoner exclaimed “why Bob, what do you mean?” Deceased replied “I’ll show you what I mean,” and struck Prisoner with gun again, the blow falling upon and breaking the breech of prisoners gun. Prisoner took Deceased’s gun away from him and threw it aside, when deceased came again at Prisoner with a knife and struck and as he did Prisoner threw his lick off with his right hand and with his own knife hurriedly drawn from a scabbard in the belt of his rifle pouch, where he kept it, stabbed deceased in the side a back handed blow, as he turned from the face of Prisoners.

Prisoner denied that he ran away when Smith sought to arrest him, and denied all ill feeling towards the Deceased and contradicted Smith in several other particulars. Prisoner further stated that after his trial and conviction in 1862, he did escape from Burke Co. jail, and went into the Federal army, and was honorably discharged from the 13th Tennessee Calvary at the close of the war.

We see that in the 1883-4 trial, Twiggs admitted that he had escaped from jail but also claimed that he had killed McCall in self-defense. Again, the jury was dismissed without rendering a verdict – eleven jurors voted to acquit, and one found him guilty. In a third trial later in 1884, Twiggs was acquitted.

His third and last trial last week resulted in his freedom. The long lapse of time and his subsequent good character aided his plea of self-defense.9

Twiggs was never penalized for escaping jail and hiding for decades. He and his second wife remained in North Carolina, settling in Mitchell County in 1885. His older children remained in Tennessee. He died on 20 August 1898 in Bakersville, Mitchell, North Carolina, at about 73-years old.

Meanwhile, the widow of the deceased, Elizabeth Sophronia Corpening McCall, had to raise her children alone after seeing much of her property sold off after her husband’s death. Widows were only entitled to a third of a deceased husband’s property. In later census records, she was found living in the households of her then married daughters. It seems that justice was never realized for McCall’s family and that night of partying in 1862 altered their lives forever.10 11

Where are they in the tree?

Sources

- 1879. [W.S. Sudderth hogs] 09 Mar: 01. https://www.newspapers.com/image/57505582/ : accessed 01 Nov 2024, The Raleigh News, Raleigh, North Carolina, online images (www.newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- 1925. “Armless, She Lived Long Life Bravely – One of Burke County’s Most Remarkable Women Is Claimed By Death,” 31 Oct: 12. https://www.newspapers.com/image/651020319/ : accessed 01 Nov 2024, The News and Observer, Raleigh, North Carolina, online images (www.newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/23583205/donnie_bristol-sudderth: accessed November 1, 2024), memorial page for Donnie Bristol Sudderth (8 Apr 1833–29 Oct 1925), Find a Grave Memorial ID 23583205, citing Forest Hill Cemetery, Morganton, Burke County, North Carolina, USA; Maintained by Bo Cash (contributor 47658683). ↩︎

- Ancestry.com, North Carolina, Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015), Ancestry.com, http://www.Ancestry.com, Burke County, Tennessee Wills and Estate Papers; Author: North Carolina. County Court (Burke County); Probate Place: Burke, North Carolina. $ ↩︎

- Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/46113338/john-twigs: accessed November 2, 2024), memorial page for John Twigs (1824–20 Aug 1898), Find a Grave Memorial ID 46113338, citing Bakersville Memorial Cemetery, Bakersville, Mitchell County, North Carolina, USA; Maintained by Glenn Ellis (contributor 47410127). ↩︎

- 1883. “After Twenty-Four Years – A Murderer Is Caught and Brought To Justice By A Detective – The Strange Story of John Twiggs,” 14 Nov: 03. https://www.newspapers.com/image/61612371/ : accessed 02 Nov 2024., The Carolina Mountaineer, Morganton, North Carolina, online images (newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- 1883. [Twiggs self-defense] 20 Dec: 02. https://www.newspapers.com/image/62000515/ : accessed 02 Nov 2024, The Anson Times, Wadesboro, North Carolina, online images (newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- In 1862, the phrase “jump the game” in the context of men playing cards likely meant to abruptly leave the game, often without paying debts or finishing hands. ↩︎

- 1884. [Twiggs acquittal] 20 Jun: 04. https://www.newspapers.com/image/61989821/ : accessed 02 Nov 2024, The Daily Review, Wilmington, North Carolina, online images (newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- “North Carolina, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-95VN-YSG?view=fullText : 31 Oct 2024), images 60-89 of 777; North Carolina. Division of Archives and History. State v. John Twiggs for the murder of John McCall., Family Search – The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (familysearch.org). ↩︎

- “North Carolina, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GGXD-CFN?view=fullText :31 Oct 2024), images 38-48 of 880; North Carolina. Division of Archives and History. 8579 State -v- John Twiggs 60 N.C. 142 (June 1863), Family Search – The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, discussion list (familysearch.org). ↩︎

Leave a Reply