This past week has been especially rough for many of us. Lucky for me, my work on the McCall book has me crawling through the details of probate records from the 1820s, 30s, 40s, and 50s. It’s tedious and occupies my brain. What I’ve found will be reported in my book but I thought I’d write a little bit about how I am going about this. Perhaps this will be helpful to other family historians and of interest to people who wonder how I can possibly spend so much time on genealogy.

When William S. McCall died in 1823 he probably believed that he was prepared and that his family would be set since he left a detailed Last Will and Testament. I wrote a little about his will when I wrote a biography of his wife Milly back in 2017.

A summary of William’s will shows that he was very specific in how his property should be divided.

“Wife Milly McCall to have 4 of her choice Negroes for the support of her and the four youngest children, and their Education. Other Negroes, land on south side of Pigg River, Waggon, 3 horses, etc., etc. to be sold and money divided among my children. Sons William S. and Thomas Fewell McCall [Thomas F. McCall not yet of age, Stokes not yet of age.] Two eldest sons not named and any others who are of age to be employed to look after the family business and property as long as they do well and no longer. Wife may lend to each of my daughters a Negro apiece, upon their giving [bond] or their return when ‘Stokes’ comes of age. Milly to receive her 2 choice Negroes, 2 horses, 2 cows, 2 feather beds, furniture, farming utensils [part] likewise the land upon which I now live or else be plentifully supported during her natural life. Even if she marries again, she is to be comfortably provided for. Friend John M. Holland, Executor [John M. Holland declined to serve on August 4, 1823 and Peter Holland qualified].”

It is not the purpose of this post to give commentary on the lifestyle of these ancestors, but yeah, it can be uncomfortable.

Anyway, William’s specificity made it very difficult for his heirs.

His oldest sons were adults when William died. They were getting married and starting their own families. The will expected them to be employed to look after the family business, but they could not expect to get any sizable inheritance until their youngest brother grew up. That brother was only two years old when the dad died, so that was a very long wait.

It got more complicated when his administrator moved out of state and had to be replaced.

It got more complicated when most of his children moved from Virginia to Missouri.

It got more complicated when several of his children died and they had their own estate administrators who had to work with the William McCall estate administrator and his replacement.

It got complicated when people started complaining and suing about things.

I have found literally hundreds of pages of information regarding the settlement of William McCall’s estate between 1823 when he wrote his will, and 1852 when his property was distributed to his heirs.

Where do I find this stuff?

People who don’t spend their time with their old dead relatives may just believe the TV commercials that show people typing a name into Ancestry.com and getting back the whole story of their family in a few simple keystrokes.

That isn’t how it really works.

Sure, Ancestry is a great place to start. It really is indispensable to this researcher and worth the big bucks it costs me to subscribe. It did, in this case, have a copy of William’s will. So, I could have stopped there.1

But, there is so much more to find if you dig deeper.

FamilySearch.org is a free site provided by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They have an unbelievable collection of information available online for FREE! It is more difficult to locate things there than searching on Ancestry, but you can find so many more things. You do need to create an account to get to things, but did I mention it is FREE?

A companion website called LDS Genealogy is very helpful. I use their directory to go to the right state and county and then can find links to specific types of records.

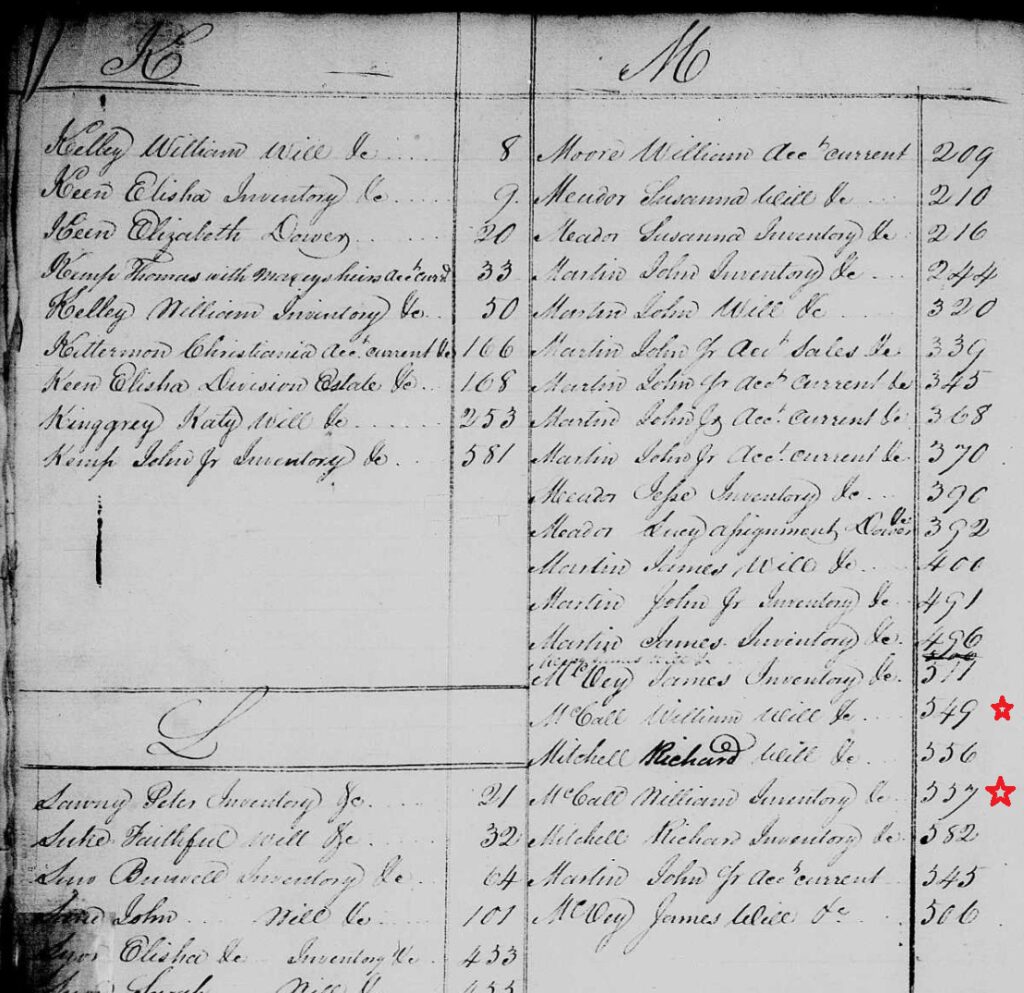

In this case, I was looking for probate records in Franklin County, Virginia, and could link to Will books, 1786-1906 ; general index, 1786-1948 in the FamilySearch Library. Those records are digitized but not electronically indexed. Since William S. McCall died in 1823, I started with the link to Will books, v. 1-2 1786-1825 and took a look to see how the records were organized. I had to scroll down a bit to find the images for Will Book No. 2 which contained the records for 1812-1825 and then had to move forward several pages to find the page that had the index for McCall records.

I was lucky this time that they indexed McCall along with the other M names. Oftentimes, Mc names have their own section in indices – sometimes showing up before the M names and sometimes after and sometimes in some other random spot. If I don’t find what I’m looking for I have to look around to see if it is hidden nearby.

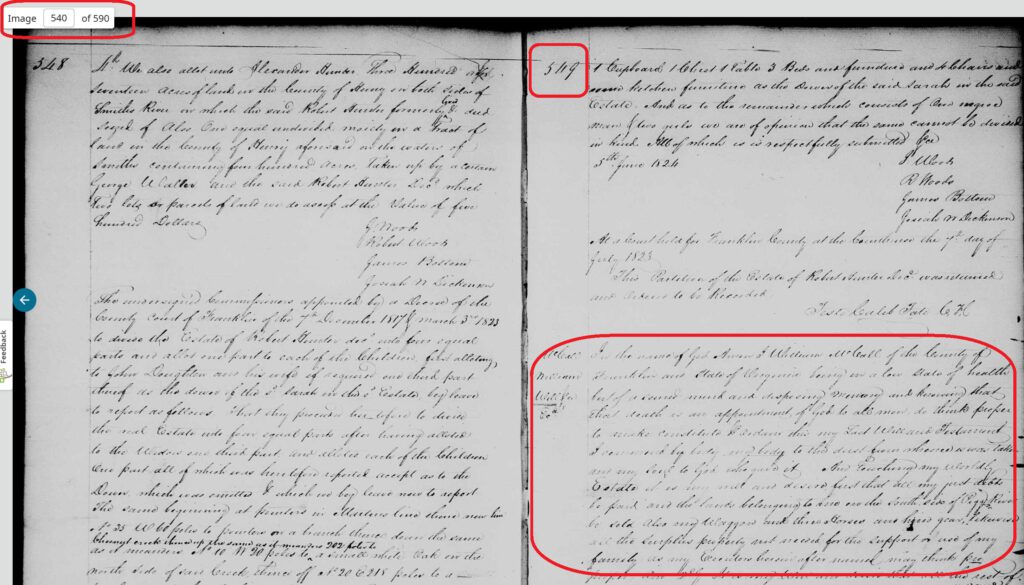

Next I had to find pages 549 and 557. These are the page numbers on the images, not the image numbers at the top of the screen.

Having found these records, I could now start harvesting information. To be fair I must note that Ancestry and Family Search both had these same records. But in my experience that is not usually the case, and it is good to look in both places.

There are a lot of things to learn from the will and from the inventory. But because I have done this for a long time, I knew that there were probably more records regarding the estate such as financial reports from the administrator and final distributions to heirs. So, I repeated my process looking in Will books beyond 1825 until I found a record that looked like a final record in the probate process. Looking on Family Search I found years and years and pages and pages of additional records related to William’s estate.

You may ask if my eyes get tired. The answer is YES.

Then there are other places to look. I only know about these because I have been working on family history for a long time. I’m not sure how I know this, but Virginia has a lot of court cases available online.2 I keep a running list of links to places that I have come across that have records that I may need someday.

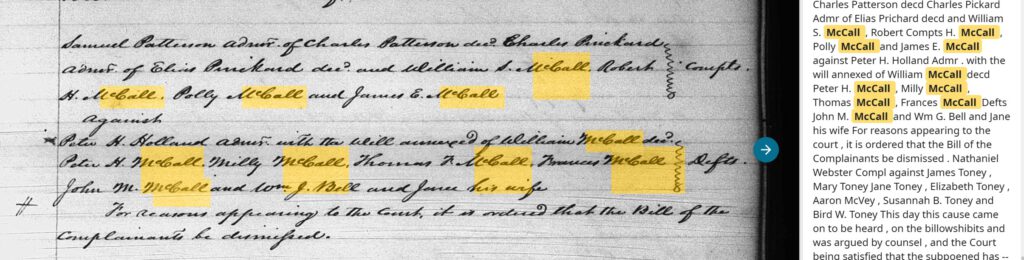

I did a search there and found four Chancery Court cases related to the estate of William McCall.

A couple showed up when I searched with McCall as the plaintiff.

More showed up when I searched for McCall as the defendant.

Since I am looking for information about William McCall’s estate and know his widow was Mildred, I know those are the records I want to look at. From there I could look at the details of the cases.

Hundreds of pages of court records!

Hundreds of pages of handwritten records in cursive.

Cursive written in the 1820s, 30s, 40s, and 50s.

Exciting but…

AI to the rescue?

What do I do with literally hundreds of pages of information on William McCall’s estate? It would fill up my book quickly if I just copied and pasted all those pages into the book. It would not be very interesting to the reader either. So, my job is to look through it all, put things in order (the files are not usually in chronological order), and try to summarize what was really happening. I probably still include more in my book than I should because it is so hard to throw little interesting tidbits away, but I do realize that normal people do not have as much tolerance as I have for the minutia.

Having spent decades of my life working in the Information Technology world, I am always looking to embrace new technologies. So, what can AI do to help?

Transkribus

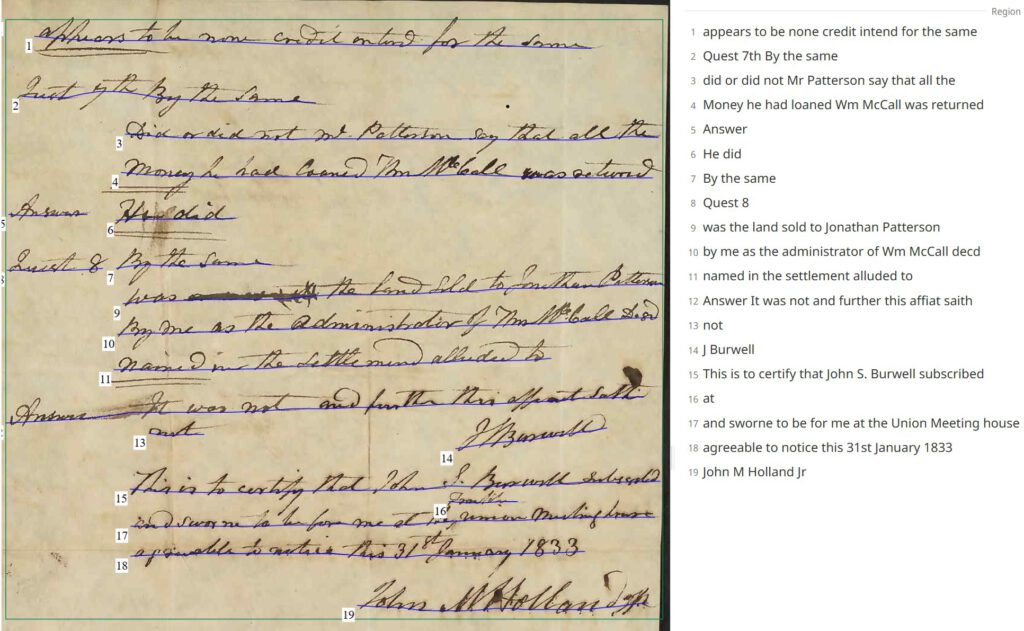

I have been experimenting with a AI transcription tool called Transkribus.

While it is not perfect, it does a great job of doing a first pass at transcription for me.

It lets me go in and correct anything within the tool. I do that sometimes.

Sometimes neither I nor Transkribus can figure out a word but usually the tool can decipher enough that I can get a gist of what is going on.

Full-Text Search

I definitely am keeping an eye on the AI for genealogy space.

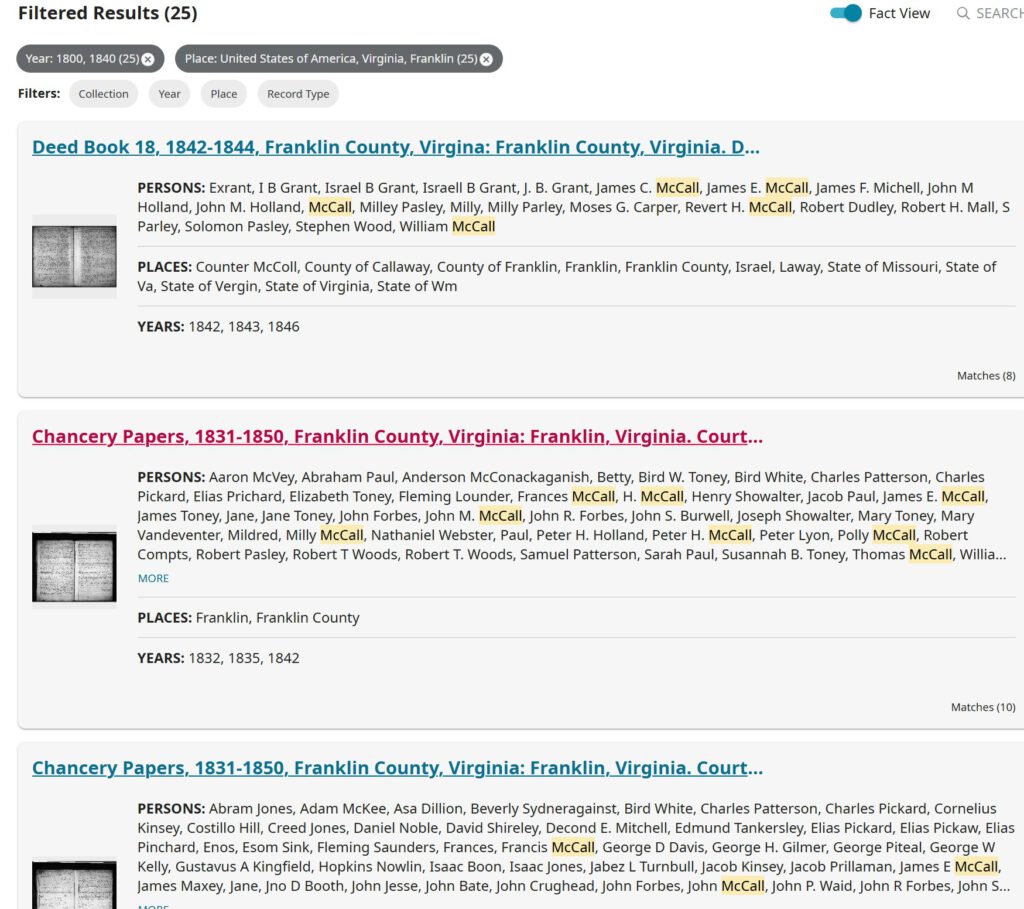

Earlier this year, Family Search introduced a new Full-Text Search feature. They are still calling it an experimental labs product and have only applied it to some of their collections thus far, but it is a game-changer. Seriously, a game-changer. I didn’t come up with that description, but it fits.

Remember earlier when I described how I found William’s will on Family Search? I had to know what I wanted to look at and then find the right set of images and then find the record set that I was interested in within that set of images and then look page by page to find William in the index and then find the right page with William’s actual records.

Well, with Full-Text Search, I don’t have to do anything that complex. I can just search on, for example, McCall, and filter on Franklin County, Virginia, as a place and 1840 as a decade and push search. Family Search has applied AI transcription to their records, and while it is not perfect, it quickly pulls together a list of things that I might want to look at.

I needed to review to see if there was anything I really wanted while trying not to get distracted when it brought up records that have nothing to do with William McCall’s estate. In other words, I needed to make myself stay focused on my current task. But it almost seems like magic how the tool can sort through millions of pages of centuries old records and find my ancestors.

When I clicked into one of the suggested documents, I found the image highlighted with my search criteria and transcribed. Amazing! I still have to use my own brain to know if this is something that really belongs to William McCall’s estate settlement and I may need to read further on the page or a couple pages back to find out a date of something, but the records are delivered to my screen like magic.

ChatGPT

Whether transcribed in Family Search’s Full-Text Search, in Transkribus, or manually by me into a Word document, there is still a lot of text to understand so that I can tell the story that I’m trying to tell.

I’ve recently been experimenting with ChatGPT.

As an example, I put the defendant’s response from Chancery case 067-1842-028 into ChatGPT and asked for a summary. I put image copies of four pages that had been handwritten in September 1838 into Transkribus and had it transcribe. I copied the raw transcription that I got from Transkribus and pasted into ChatGPT with a request to do a summary.

I was actually very amazed at how well it did with less than perfect transcription, old words, and a complex document.

While ChatGPT has been found to make things up, I found that it did a really good job for me. Yes, I fact checked it by reading the actual documents myself. Before using it in the book, I will make tweaks and try to match it to more closely to my style of writing, but I feel like I saved a lot of time.

Before I get back to work on William McCall and family I’ll leave you with one more thought on AI.

I asked ChatGPT to create me a picture to add to this post. I asked for “an abstract impressionist charcoal drawing style of a modern-day female genealogist with curly hair just down to her shoulders working at her two large computer screens studying hundreds of pages of old court records from the 1840s.”

I asked for modern clothes, but I guess the picture is how AI thinks I dress. Nope. And my hair is not nearly that long anymore.

We’ll have to check back in another decade to see how far AI has come – though it will be more than a little creepy if in the future it comes up with a picture that actually looks like me and knows what I’m wearing.

Sources

- Ancestry.com, Virginia, Wills and Probate Records, 1652-1983 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015), ancestry.com, Will Books, 1786-1906; General Index, 1786-1948; Author: Virginia. Circuit Court (Franklin County); Probate Place: Franklin, Virginia. $ ↩︎

- Library of Virginia, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/default.asp#res. ↩︎

Leave a Reply