My time for family history was limited this week and will likely be non-existent next week. There used to be a time when I was very excited for time off work, but now that I do something I love, I feel a little sad when it is time to take a break. When the guests arrive and the Thanksgiving holiday is underway it will be great but during the planning, cleaning, and cooking parts of the holiday I’ll admit I’m longing to be with my old dead ancestors instead.

The time I did have to spend with my McCall family this week was mostly a continuation of study of William McCall’s probate proceedings. I found myself thinking a lot about how Mildred Holland McCall, the widow, was affected by the legal system of her day.

Why make it so hard for Women?

As background, I will share that I have been an advocate for women’s rights throughout my life. I worked in what ended up being a male-dominated profession and often found myself as the only woman in the room. Though it was about 50% men and 50% women in Computer Science at my university, in the real world, women did not flood to the profession and, in fact, I saw an exodus of women from the field at one point in my career. The stereotypical computer person now is definitely a nerdy man rather than a woman. The women I worked with were usually as good at what they did (or more so) than their male counterparts.

In my opinion, it shouldn’t matter whether you are a woman, man, non-binary, or any other gender identity as long as you are competent in your field. But because the men did not always make things easy for me, I could tend to get a little snarky (and, well, tired – it is exhausting having to prove yourself and having to fight to be equally included). Early in my career I was gifted the following plaque which has always been on my desk.

I’ve written a few posts that show my disappointment in how long it has taken for women to have any rights.

I was appalled when I learned that my paternal “grandmothers” were not allowed to vote in their church until 1951. Before that, they just had to wait in the church basement while men decided things. With how active women are in my church, I cannot imagine having only men in charge. It was a different time.

In that post, I included a list of things that women gained the right to do – in my lifetime. I still cannot believe that women couldn’t get their own credit cards until 1974 and you could still lay a women off for being pregnant until 1978. To me it seems barbaric.

It bothers me still that our female ancestors did not have the right to vote in the US until 1920 – you can read some of that history in my series of posts in recognition of the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

This week I got ticked off again the more I learned about what Mildred Holland McCall and her daughters had to go through regarding the estate of husband and father, William S. McCall.

By the way, streaming the movie Widow Clicquot this weekend did not help my mood regarding women’s rights. The movie shows it was not good for women in France back then either (we enjoyed the movie, in case you are wondering).

I’ve written a bit about this before, but as a refresher…

- William died in Franklin County, Virginia, in 1823 and left a will with stipulations that his estate property would not be fully distributed until his youngest child became an adult, thus ensuring the estate would be tied up in the court for a couple decades.

- William was very specific on what pieces of his property his widow could use and what property should be sold or given to their children.

Coverture

In the 1800s, the legal of doctrine of coverture meant that married women generally had no right to own property. When a woman married, her legal identity was merged with her husband’s, severely limiting her ability to own property, manage finances, or make legal decisions independently. Married women could not own real estate. Any income a woman earned belonged to her husband. Any property or money that a wife inherited during marriage was controlled by her husband.

When William McCall died, his daughters were single. As soon as each of them married, she lost their right to their inheritance and instead it belonged to and was managed by her husband. When the husband died, court-appointed administrators – sometimes the County Sheriff – would be assigned to take care of things on behalf of the woman. The ladies weren’t allowed to have a say in what was done with their property. All the men assigned to help the women got a cut of the estate through administrators fees and such.

Dower Rights

When her husband died, a widow had dower rights. The law dictated that she was entitled to use one-third of her deceased husband’s real estate. She could use the property during her lifetime, but could not sell it or fully control it. The other two-thirds passed to her children. Additionally, unless her husband’s will said otherwise, she normally had to give up use of that property if she remarried.

If the husband left a will, he might name an executor to handle the estate. If no will existed, the court would appoint an administrator. Often, the executor or administrator was a male family member.

If a widow received funds or property, she often remained under the court’s oversight, especially if she was caring for minor children.

To try to put it in perspective, imagine a young couple marrying. Let’s say they both came to the marriage with their own car and they moved into the townhouse that she had bought before they married. If the same coverture laws existed now, that car and townhouse that the bride bought before she was married would become the groom’s property. Not jointly owned property, but the solely the groom’s property.

Let’s pretend that he passed away right after they had their first child. Assuming the young husband didn’t have a will, the court would appoint an administrator – perhaps a brother of the husband or wife. That administrator would get to decide if either or both of the cars should be sold. The administrator would decide if the townhouse should be sold. If they wanted to sell the property it would happen and she she would get 1/3 of the proceeds. But she would not be allowed to manage that money, for example to get herself a junker so that she could have transportation or to buy a smaller place to live. The administrator would decide when and if she got to have any of that money and how it could be used. The child would inherit the other 2/3 of those car and house sales, but again the money would be doled out as the administrator saw fit because the child was a minor. The courts would be involved monitoring the administrator for the next couple decades until the child was a legal adult. The court fees and administrator fees would be taken out of the estate. Argh! It is awful to imagine living under those constraints!

In Milly’s case, the personal property of her deceased husband was valued at $3,139 when an inventory was taken on 20 September 1823. It was a sizable amount of personal property. Relative worth of old money can be measured in several ways. $3,138.90 in 1823 would have the same purchasing power as $97,619.48 in 2024. In terms of wealth held, $3138.90 then would be equivalent to $3,776,195 in 2024.1 This did not include his real estate.

After William’s death, Milly was only entitled by law to use one third of that wealth.

Oversight and no Control

In William McCall estate, the executor William named (Milly’s brother) declined to serve and someone else (Milly’s nephew) stepped in to serve instead. Milly was about 43-years old when her husband died. Her nephew was only about 25. While I love my brothers and my nephews, I cannot imagine having one of them controlling my business and finances. It was the way things were then, I suppose, and maybe Milly couldn’t imagine things being any different, but I would have found it frustrating.

I would have also been very frustrated when parts of my property were sold off. Maybe Milly still need the yoke of oxen and wagon and other things that the administrator decided wasn’t needed. But back then even though they were a married couple, everything was considered William’s property and Milly had no right to it.2

… the lands belonging to me on the South side of Pigg River be sold Also my Waggon and three horses and hind gear, likewise all the surplus property not needed for the support or use of my family as my Executors herein after named may think proper…3

When her youngest children became adults, per the will, parts of the estate were sold off. When William wrote his will he likely theorized that Milly wouldn’t need as much property when she no longer was raising the children. A sale on 07 August 1843 netted just over $3,400. Milly had to go to the sale to buy some of the things she still wanted (or needed) such as a bull and a couple cows and calves. She spent $210.4

More Inheritence

When Milly’s dad died, she was already a widow. Often, a widow could have greater property rights than a married woman and would have been able to own what she inherited from her father. However, Milly’s dad specified in his will that a male would manage the shares that Milly and her sister received. Again, someone, in this case Milly’s brother, was doling things out to Milly. He made decisions to invest some of her inheritance rather than giving her the funds. Because, of course a woman wouldn’t make good decisions on her own – right? (sarcasm)

Women and Business

We know that Milly did know what was going on with the business of her plantation. When the second administrator of William’s estate (the first one left the state and another was appointed) was being sued for not necessarily doing things on the up-and-up, Milly participated in the review of the accounting books and was able to call the plaintiff out, for example, reminding him that “he well knew” something regarding rental property.5

In the agriculture schedule from the 1850 Federal Census (27 years after the death of her husband) we see that Milly had managed her plantation in producing 500 pounds of tobacco, 250 bushels of Indian corn, 100 pounds of butter, 25 bushels of wheat, and 20 bushels of oats, as well as other products. She was 70-years old by then, but still making things happen.

However, because Milly was running property tied to her late husband’s estate, it was subject to the administration of the estate. The estate administrator managed the assets. Estate accounting shows regular payments to Milly, so she might have been receiving an income or allowance, but surely had to go to the administrator for funds to pay her plantation related bills.

Left with Little

Before she died, her dower property was sold. Whether it was Milly’s idea or the idea of some of her sons and sons-in-law we can’t know for certain (I have my guesses though), Milly and some of her heirs sued to obtain a decree for the sale of her lands and property even though she hadn’t yet died.6 The 1852 legal notice published in the Lynchburg Virginian said that “the said Mildred McCall wishes said sale and distribution to be made.“7

The sale happened and the records show that in order to keep some of what we might think of as her property (but back then wasn’t legally hers since it was still considered her late husband’s property), she had to buy it at the sale. The proceeds of the sale were then distributed to her husbands’ heirs which by then included Milly’s still living children and her grandchildren who were children of her deceased children.

When Milly died a couple years later, on 14 April 1854, her total assets in Franklin County, Virginia, totaled $99.61 – $88.36 in cash and $4.25 interest due on a bond (loan) her son had taken in order to by property at her dower sale. She died while visiting children in Callaway County, Missouri, and had some property with her there – a bedstead, bed and bedding, bedclothes, a coffee mill, a tea kettle, a frying pan, a pot, and a bucket, along with $30 cash.

Women’s Property Rights

During Milly’s lifetime, some places in the United States were considering allowing women to own property. Mississippi was the first to pass a Married Women’s Property Act in 1839. This allowed women to own property brought into the marriage.

Another of our ancestors, Margaret Woods Fawcett owned property in Iowa in 1853. She had inherited money and gave her husband, Simeon, $3,000 to buy land. He bought the land and put it in his own name. Iowa had passed a law in 1851 requiring married women to register their own property in their own name. if they didn’t do so within five years of acquiring the property, it was legally assumed that the property belonged to the husband. So Simeon deeded the property to Margaret (with the caveat that she could not sell it without his agreement until at least two of the children were of legal age).8

A year after Milly died, in 1855, Missouri passed its Married Women’s Property Act. This law granted married women the right to own property separately from their husbands and retain control over their earnings and inheritances.

It was not until the 1870s and 1880s, decades after Milly’s death, that most U.S. states had passed similar laws.

Virginia didn’t enact its Married Women’s Property Act until 1877. This act allowed married women to own and control property in their own name, including property inherited or earned during marriage. It marked a shift away from the doctrine of coverture, which had previously given husbands control over their wives’ property.

These laws were part of the bigger social and legal shifts happening in the 19th century as people’s views on women’s rights and independence started to change. But actually putting these rights into practice often fell behind, since societal norms still made it hard for women to fully take control of their own lives.

The last U.S. state to grant property rights to married women was Louisiana. Their legal system was based on the Napoleonic Code. Under this system married women were considered part of a community property regime, but the husband had exclusive control over community property during the marriage, and while women could own separate property, in practice, their rights to manage it were severely limited.

Remember that movie I mentioned watching? Widow Clicquot9 was living in the time of Napoleon so felt the full wrath of that Napoleonic Code at its inception.

In 1979, Louisiana became the last state to have its Head and Master law struck down. They appealed to the Supreme Court in 1980 and in 1981 the court declared the practice of male rule in marriage unconstitutional.10

Ladies, read that again – 1981. Decided by the US Supreme Court. Am I the only one a little worried? Forgive me for my snark and sarcasm, but as I study the lives of William and Milly McCall, I can’t help but feel compassion for Milly and the other women of her time. I am appreciative of the rights that we have today – and hope that never changes.

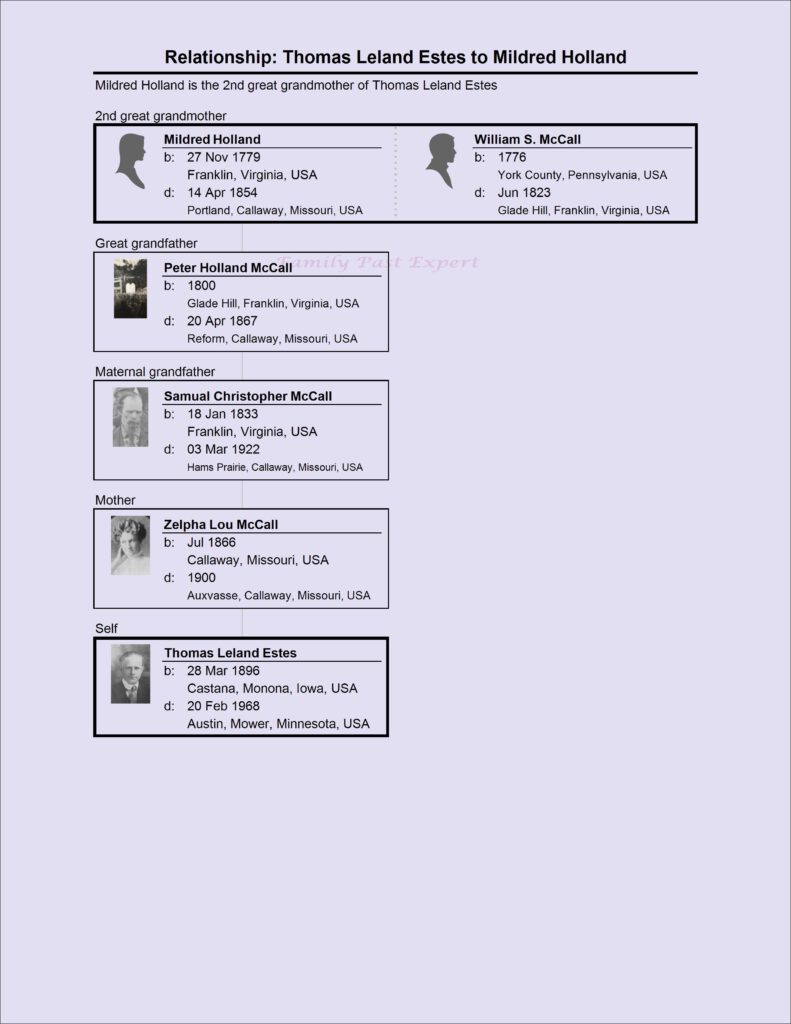

Where is she in the tree?

Selected Sources:

- Purchasing Power Today of a US Dollar Transaction in the Past,” MeasuringWorth, 2024; www.measuringworth.com/ppowerus/ : accessed 20 Nov 2024. ↩︎

- Franklin, Virginia, Jonathan Patterson vs ADMR OF William McCall; Index Number: 1839-007; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=067-1839-007 : accessed 05 Apr 2024; digital images, Library of Virginia, Virginia Memory (lva.virginia.gov/chancery) ↩︎

- Franklin, Virginia, Jonathan Patterson vs ADMR OF William McCall; Index Number: 1839-007; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=067-1839-007 : accessed 05 Apr 2024; digital images, Library of Virginia, Virginia Memory (lva.virginia.gov/chancery) ↩︎

- Franklin, Virginia, Robert H. McCall v Mildred McCall ETC; Index Number: 1851-032; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=067-1851-032 : accessed 05 Apr 2024; digital images, Library of Virginia, Virginia Memory (lva.virginia.gov/chancery). ↩︎

- Franklin, Virginia, Jonathan Patterson vs ADMR OF William McCall; Index Number: 1839-007; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=067-1839-007 : accessed 05 Apr 2024; digital images, Library of Virginia, Virginia Memory (lva.virginia.gov/chancery). ↩︎

- Mildred McCall ETC PETITION OF Charles Pinkard ADMR v Peter H MCCall ETC. 1857. 1857-002 (Chancery Court, Franklin County, Virginia). Accessed 04 05, 2024. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=067-1857-002. ↩︎

- 1852. “Virginia,” [McCall et al v McCall et al] 09 Aug: 03. https://www.newspapers.com/image/900603765/ : accessed 12 Sep 2024, Lynchburg Daily Virginian, Lynchburg, Virginia. $ ↩︎

- You can read much more about the Margaret and Simeon in my book The Fawcett Family. ↩︎

- “Madame Clicquot Ponsardin” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madame_Clicquot_Ponsardin : accessed 20 Nov 2024. ↩︎

- Kirchberg v. Feenstra, 450 U.S. 455 (1981) https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/450/455/ ↩︎

Leave a Reply