With the holidays behind me, I’ve been slowly getting back to working on my McCall book. This week I have been spending most of my time back in Callaway County, Missouri, and nearby places, learning about children and great-grandchildren of third-great aunts and uncles.

Besides many new cases of consumption, I’ve been running into a fair number of Confederate soldiers. Because telling their stories in detail is outside the scope of my book, I’m sharing here what I learned about a couple of these characters whose war days seem to have been their glory days — cue Bruce Springsteen’s song.

Callaway County and the Civil War

A lot of the people who settled in Callaway County, Missouri, came from places like Virginia and other Southern states. They moved west in the early 1800s, looking for good farmland and new opportunities. But they didn’t just bring their farming skills—they also brought their way of life and beliefs. Many of these settlers relied on enslaved labor and thought that states should be allowed to continue slavery if they wished.

By the time the Civil War rolled around, Callaway County had a lot in common with the Southern states, especially when it came to farming and slavery. Families there saw the Union’s push to end slavery as a direct attack on how they lived and worked, so it’s no surprise they leaned toward the Confederacy. They used the phrase “states’ rights” largely as a euphemism for the right of states to allow and regulate slavery and argued that the Federal government had no authority with the decision to maintain slavery as an institution.

On top of that, a lot of folks in Callaway still felt connected to the South because of family ties or old traditions from places like Virginia. Those connections made it easy to sympathize with the Confederate cause and resist Union efforts. That’s one big reason Callaway County became part of Missouri’s “Little Dixie,” a region known for its Southern roots and Confederate loyalties.

Callaway County, Missouri, was right in the middle of the chaos during the Civil War, just like the rest of the state. People in the county were split—some backed the Union, while others supported the Confederacy. Early in the war, in 1861, Southern supporters in Callaway put together a militia, which led to a standoff with Union troops. This is when the county earned its nickname, the “Kingdom of Callaway,” because local leaders struck a deal with the Union to stay neutral and avoid being occupied. Even with the truce, the area stayed tense.

The war brought guerrilla fights and raids to Callaway County, with Confederate bushwhackers and Union militias clashing regularly. Civilians had a rough time, dealing with destroyed property, loss of life, and being forced to take loyalty oaths. The county sent soldiers to both sides, which split families and communities even more. By the time the war was over, Callaway County, like much of Missouri, was left battered and divided, with scars from the violence and bitterness that would take a long time to heal.1

Many Confederates believed in their cause for the rest of their lives.

Confederates in the Family Tree

Since most of our McCall family came to Missouri from Virginia, and some family members were still there, it is probably no surprise to know that most (if not all) of them were Southern Sympathizers. I’ve written in the past about our direct ancestor Samual McCall who fought for the Confederacy and his mother, Mildred Holland McCall, who lived her life dependent upon the institution of slavery.

It should be no surprise that most of the family and extended family supported the Confederacy.

Uncles

McCall uncles in the Confederate Army included Milly’s son, John Meador McCall and Sam’s brothers John William “Buck” McCall, Robert Henry McCall, and James Franklin McCall.

Buck and Robert were with Company B of the 1st Calvary. Records show that Buck spent most of his time caring for the company’s horses.2 Robert was not as lucky. He fought at Lexington, Bentonville, Elkhorn, Farmington, and Corinth before being captured at Big Black Bridge in May 1863. He was carried to prison in Fort Delaware, Delaware. He was moved from there to Point Lookout, Maryland, and ended up taking an oath of allegiance to the United States before being released in March 1864.

John Meador McCall spent time at Fort Delaware, Delaware, too. Shortly after his nephew Robert was released, he arrived. John was the son who remained in Virginia with his mother so he fought for Virginia. He enlisted at Glade Springs, Virginia, on 25 April 1861 and served with Company F of the 37th Virginia Infantry Regiment. By mid-1862, he had been promoted from Private to Corporal. Then on 12 May 1864, he was captured at Spotsylvania, Virginia, and sent to the prison at Fort Delaware. When the war ended, after signing an oath of allegiance to the United States, John was released on 20 June 1865.3

Fort Delaware was located on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River. Originally a fort, it was repurposed as a prison. It became one of the largest prisons housing 12,000 at its peak. Its capacity was much lower than that. Conditions were harsh. Prisoners faced overcrowding, disease, inadequate food, and poor sanitation. While the prisoners were treated relatively well, there was still a high death rate and because Pea Patch Island was isolated, it did not always have adequate supplies.4 5

Cousins and In-laws

McCall cousins who fought included James Henry Bell who fought with one of the Callaway County companies, William S. Gilbert who served under General Price, and William Wyatt Smith who like his cousins Buck and Robert, was with Company B of the 1st Calvary.

McCall in-laws who served in the Southern cause included Caleb Berry, Samuel A. Smith Craghead who achieved the rank of Corporal, James Hiram Goodrich, Thomas Charles Holland, Stephen Henry Olmsted, and William Patterson who did not move to Callaway County but rather led one of the first companies from Franklin County, Virginia, as a Captain in Company G, 57th Virginia Regiment, Infantry, which was nicknamed the “Ladies Guard.”6

While this is not an exhaustive list – we have many Confederate soldiers in the family tree. And, like was stated above, that is probably no surprise. But, it may be surprising how long after the war they continued to applaud and support the cause.

An Escapee

Stephen Henry Olmsted was born in August 1839 in Jersey County, Illinois. Without doing a lot of research into his lineage (since he is just married into the McCall family), it appears that he and a younger brother were orphaned and raised by Peggy and Joseph Crabb, who were presumably grandparents, in Delhi, Jersey County, Illinois, not terribly far from St. Louis, Missouri.

While Illinois was a free state and the state of Lincoln, not everyone there supported the Union. Olmsted was just reaching adulthood when the war broke out. For whatever reason, he joined the Confederate Army.

Serving with Shelby

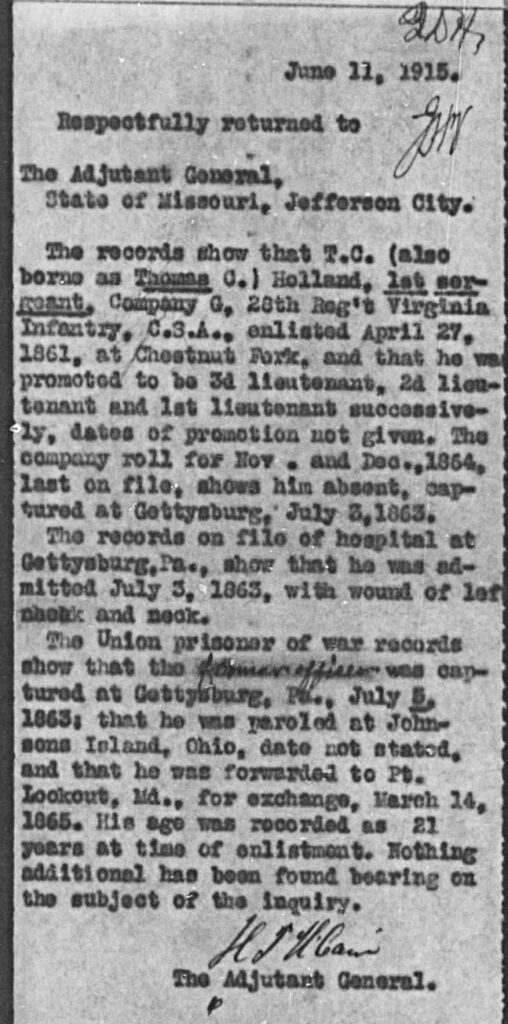

According to his obituary, he was with General Joseph Shelby‘s journey to Mexico at the close of the war.

After the Civil War ended in April 1865, General Joseph O. Shelby wasn’t ready to give up. Rather than surrender to Union forces, he and about 300 of his men—known as “The Iron Brigade” or “The Missouri Iron Brigade”—decided to head to Mexico to start over. They didn’t want to live under Union control and figured Mexico might offer them a fresh start.

In June 1865, Shelby and his troops made their way south, taking what was left of their Confederate identity with them. When they reached the Rio Grande, Shelby sank his Confederate flag in the river, symbolizing the end of that chapter of his life. Once they crossed into Mexico, they offered their military skills to Emperor Maximilian I, who was fighting to hold onto power with French backing.

Maximilian welcomed Shelby but politely turned down his offer to form a Confederate army for him. After that, Shelby’s men split up—some stayed in Mexico to start new lives, while others eventually returned to the U.S. Shelby himself went back to Missouri, settled into farming, and later became a U.S. Marshal under President Grover Cleveland, which shows there was not much penalty for being a former Confederate general.

Shelby’s journey to Mexico became one of the most famous stories from the end of the Civil War, showing just how hard some Confederates found it to let go of the fight.

Before their trip to Mexico, among other activities, the Iron Brigade wreaked havoc in Sedalia, Missouri. In the fall of 1864, General Joseph O. Shelby and his Iron Brigade were part of a big Confederate push into Missouri during Sterling Price’s raid. On 15 October 1864, about 1,500 of Shelby’s cavalry surrounded the town of Sedalia, which was lightly defended by Union militia and rumored to have thousands of mules and cattle which would be helpful in feeding hungry Confederate forces. Shelby’s men quickly overran the town and took control.

Once they had Sedalia, things got rowdy. The Confederate troops started looting stores, homes, and other buildings, grabbing supplies and causing chaos. Raiding like this was pretty common, especially since it disrupted Union operations and helped the Confederates resupply themselves.

But the looting didn’t last long. General M. Jeff Thompson, another Confederate leader, showed up and put a stop to it. He got the troops back in line and moved them out of Sedalia. The Confederates didn’t stick around long enough to hold the town, and Union forces regained control not long after.

This raid on Sedalia was just one part of Price’s larger plan to take Missouri back for the Confederacy. In the end, the campaign didn’t succeed, but it caused plenty of trouble for the Union while it lasted—and gave Shelby’s men another story to tell.

Capture and Escape

Somewhere along the way, our relative Stephen Henry Olmsted was captured.

His obituary told that he was shackled – with ball and chain – and put on a train headed to the Union prison in Alton, Illinois, near his hometown. Conditions in the prison were harsh and the mortality rate was above average for a Union prison. Perhaps, Olmsted knew the reputation of the place and was very motivated to not arrive there. While enroute, he jumped off the moving train, and escaped in the brush. He was able to remove his chains and escape.7

Decades after the war he married Mary Winifred Stucker a Callaway County, Missouri, native and McCall descendant who was twenty years his junior. She was probably his second wife. Together they had three children and lived in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri – the same town he probably helped ravage during the war.

Olmsted died in 1904 at the age of 64. His death came 39 years after the end of the Civil War. He had married (probably twice), worked as a machinist, and raised a family. Yet, the bulk of his obituary was devoted to telling his stories from the Civil War. There was only a brief mention that he had survivors.

The stories of fighting, capture, and escape were probably stories that he loved telling a lot. We can imagine the tale getting more exciting each time it was recited. We might imagine the old soldiers huddling over a drink and a smoke to relive their glory days. Clearly, there was no shame or embarrassment for having fought for the wrong side.

Confederate to the End

Thomas Charles Holland was proud of his Confederate service too. He was born 16 February 1841 in Bedford County, Virginia. He was likely a 2nd cousin of our ancestor, the aforementioned Mildred “Milly” Holland McCall. This researcher has not yet tackled a full study of the Holland family, but initial analysis indicates that Thomas Charles was a great-grandson of Peter Holland Sr. who was also Milly’s great-grandfather. But I ran across him this week because he married a McCall descendant, Vara Sparrell Stucker who was a great-granddaughter of Milly. Yes, if I’m right then Thomas and Vara were related – 3rd cousins 2x removed.

Endogamy: The practice of marrying within a specific social, cultural, or geographical group, which can contribute to repeated family intermarriage over generations.

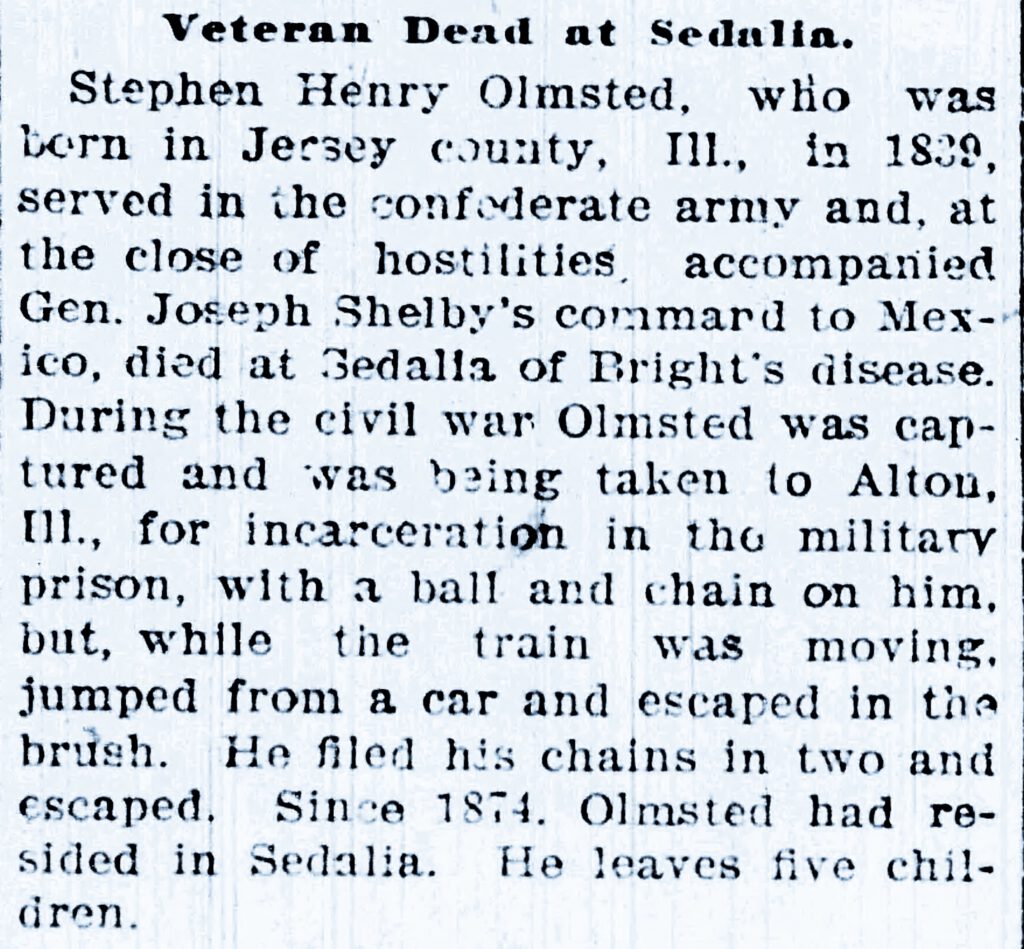

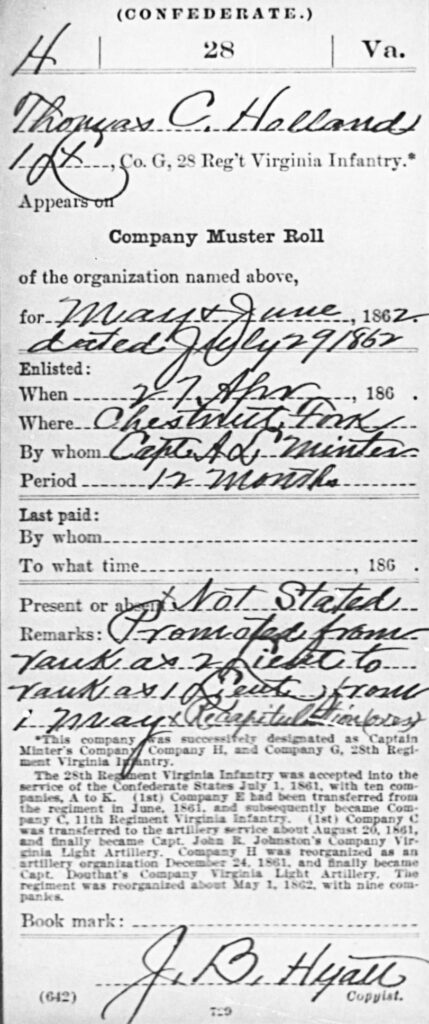

A decade before he married, Holland served four years in the Confederate army and was Captain of Company H, 28th regiment of Pickett’s Division of Longstreet’s Corps Army of Northern Virginia.8

Well, maybe?

While that is what the newspapers said time and time again, the service records that have been found only show him reaching the rank of 1st Lieutenant.

Records from the 28 Regiment Virginia Infantry indicate that he entered service as a 1st Sergeant on 27 April 1861 at Chestnut Fork, Virginia. The records show he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant on 05 June 1861, and to 1st Lieutenant on 01 May 1862. On 27 June 1862, he was sent to the hospital for some wounds and was then absent from service in July and August. He returned to camp on 31 October 1862 and signed the rolls as the commander of the company.

The Battle of Gettysburg

Thomas C. Holland was one of the survivors of Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg.

“Pickett’s Charge was a monumental disaster for the Confederacy”

He survived but was not unscathed.

He was wounded in the left cheek and neck.

And worse, he was captured.

A summary of his service indicates that he got attention at the hospital in Gettysburg on 03 July 1963 – the day of Pickett’s Charge.9

He was then captured by the Union Army at Gettysburg on 05 July 1863.

After the Confederate retreat, they left behind thousands of wounded soldiers who could not be transported due to the severity of their injuries or logistical challenges. These prisoners became prisoners of war.

The Union treated the wounded Confederates with the same care as their own soldiers, as medical ethics of the time emphasized treating all wounded, regardless of allegiance. Many Confederate prisoners were later transferred to Union prison camps once they were stable enough for transport.

Prisoner of War

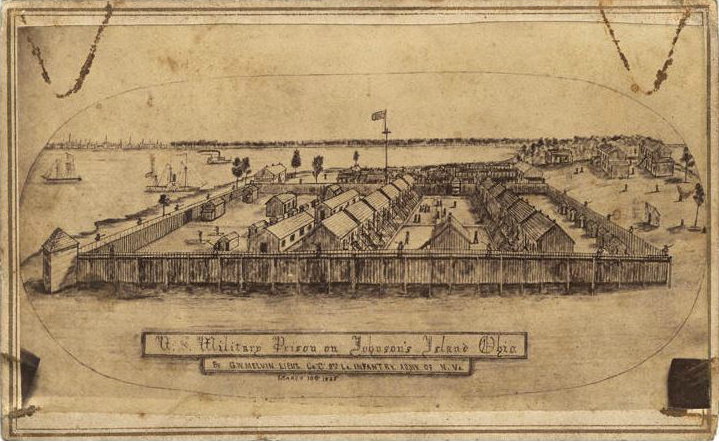

Holland was one of them. He was imprisoned at Johnsons Island, Ohio. The prison camp was on an island in Lake Erie, off the shore of Ohio. Lucky for Holland, Johnson’s Island had one of the lowest mortality rates of any Civil War prison.

The facility was originally set up to hold captured Confederate officers, but eventually received privates, political prisoners, and spies too. Brigadier-General M. Jeff Thompson, a senior officer of the Missouri State Guard served time there while Holland was imprisoned (the same M. Jeff Thompson mentioned earlier).

While winters were bitterly cold, food was limited, and morale could become low due the monotony of prison life, Johnson’s Island was not the worst place a war prisoner could be. The inmates were not generally forced to work other than light duties like keeping their barracks clean and could spend their time writing, crafting, and playing music to pass the time.

Eventually, Holland was moved to Point Lookout, Maryland, for a prisoner exchange on 15 March 1865. We do not know how long Holland was at Point Lookout. It was not a nice place. It was overcrowded, had poor living conditions, bad sanitation, and soiled water. Hopefully for him, his arrival there was close to his release date.

The war ended on 09 April 1865.

Life after War

Thomas Charles Holland came to Missouri in 1865 and married to McCall descendant Vera Sparrel Stucker on 27 October 1873. He lived in Callaway County until 1883, moved to Sedalia where he lived until 1907, lived at Kansas City until 1913, then moved back to Callaway County where he lived with his children at Reform. Census records show him working as a store clerk, and later as a real estate agent.

United Confederate Veterans

According to his obituary, his greatest enjoyment in the latter years of his life was attending the reunions of the old veterans.

Holland became very involved in the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) organization. He was widowed in 1885 so probably had plenty of time for his own pursuits. The UCV was founded in 1889 and Missouri likely had a chapter soon after. The group sought to foster camaraderie among veterans, memorialize Confederate soldiers, provide support to veterans and their families, and to promote a version of Civil War history sympathetic to the Confederacy – think the Lost Cause narrative. They held annual reunions which were major events in Southern States and were responsible for raising funds to erect Confederate monuments.

The Lost Cause narrative is a post-Civil War interpretation of the Confederacy that romanticizes its motives and minimizes the role of slavery as the central cause of the conflict. Emerging in the late 19th century, it portrays the Confederate cause as noble, its leaders as heroic, and its soldiers as honorable defenders of states’ rights and Southern culture against overwhelming Northern aggression. This narrative downplays the Confederacy’s defense of slavery, framing it instead as a fight for constitutional principles and regional autonomy. The Lost Cause influenced historical memory through monuments, literature, and organizations like the United Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy, shaping public perceptions of the Civil War, particularly in the Southern United States.

People referred to Holland as Captain. While he may not have officially achieved that rank while in service, it was not uncommon for veterans to be given honorary titles by their communities – or friends – or maybe even themselves.

In 1921, Holland was elected Brigadier General Commander of the Eastern Missouri Division of the UCV at the Missouri state meeting in Sedalia. The group’s national reunion that year was held at Chattanooga, Tennessee. The railroads even offered attendees reduced rates to get there.10

In addition to his involvement in the UCV, in 1923, Holland received the appointment of Missouri trustee of the Confederate Memorial Institution at Richmond, Virginia, a property valued at the time at more than $500,000. There was only one trustee from each of the Southern states and one from the District of Columbia. Captain Holland’s appointment was for life.11

That appointment was a big deal and most likely happened because of his prominence in the UCV. Trustees were responsible for advancing the museum’s mission to memorialize the Confederacy, collect and preserve artifacts, documents, and memorabilia, and promote the Lost Cause narrative. Trustees often played a key role in fundraising.

In 1924, at his last reunion of the Missouri division of the United Confederate Veterans, Holland continued to serve as a Brigadier General in the organization.

A speaker at that event, nearly 60 years after the war, spoke about “Jeffersonian democracy and the high-minded patriotism of such men as Robert E. Lee were extolled.” The speech condemned socialism as “the chief menace to our government” and claimed that descendants of Confederate soldiers would never be conscientious objectors or bolshevists. It also claimed that 60% of the officers in the US army at the time were Southerners.

Meanwhile, Gen. Thomas Charles Holland’s remarks were lighter. When addressing a group of Daughters of the Confederacy, he said, “Hot biscuits provide the secret of how to live to a good old age.” At 83-years old, he joked, “Of course, I am not old enough to show that yet but my mother died a few years back at the age of 104. She used to eat hot biscuits twice a day without fail and I reckon she would have lived to 150 years old is [sic] she had eaten them three times a day.“12

Thomas Charles Holland died on 11 February 1925, at the age of 83.

As the old soldiers aged and passed away, membership in the UCV declined. The last official national reunion was held in 1932 and the organization officially disbanded in 1951 following the death of its last known member. The group’s legacy is continued now through the Sons of Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy organizations.

The Confederate Memorial Institution was consolidated into what is now the American Civil War Museum which focuses on providing a comprehensive and inclusive history of the Civil War covering the Union and African American perspectives in addition to Confederate history. In recent years, there has been a significant movement to reassess, and in many cases, remove Confederate monuments due to racism and white supremacy.

However, Thomas Charles Holland is remembered and the memory of his time as a Confederate soldier lives on. In a 2011 article in the Kansas City Star, one of his 3rd great-grandsons showed the reporter the Confederate flag that once draped Thomas Charles Holland’s coffin and was quoted defending flying the Confederate flag.13

Where are they in the tree?

Sources:

- “Callaway County Becomes ‘The Kingdom,’” Kingdom of Callaway Historical Society (https://www.callawaymohistory.org/community-histories : accessed 16 Jan 2025). ↩︎

- “Carded Records Showing Military Service of Soldiers Who Fought in Confederate Organizations”, digital image, The National Archives (fold3.com), John W. McCall, https://www.fold3.com/image/88575563/mccall-john-w-34-page-1-civil-war-service-records-cmsr-confederate-missouri : accessed 15 Jun 2023. $ ↩︎

- Carded Records Showing Military Service of Soldiers Who Fought in Confederate Organizations”, digital image, The National Archives (fold3.com), John M. McCall, https://www.fold3.com/file/13601388/mccall-john-m-page-1-us-civil-war-service-records-cmsr-confederate-

virginia-1861-1865 : accessed 19 Jan 2025. $ ↩︎ - “Fort Delaware,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Delaware : accessed 19 Jan 2025). ↩︎

- “Fort Delaware Prison,” VA (https://www.cem.va.gov/docs/wcag/history/signs/Finns-Point-National-Cemetery-NJ-Confederate-Burials-Interpretive-Sign.pdf : accessed 19 Jan 2025). ↩︎

- Marshall Wingfield, Franklin County, Virginia: A History: (1964; reprint, Baltimore, Maryland: Clearfield Company, Inc., 1996, 2003); Company G, 57th Virginia Regiment, Infantry, pp. 157-8, 173. ↩︎

- “Veteran Dead at Sedalia,” 28 May: 03. https://shsmo.newspapers.com/image/957127867/ : accessed 15 Jan 2025, St. Louis Palladium, St. Louis, Missouri, online images (newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- “Confederate Veteran Dead – Thos. C. Holland Died Very Suddenly Wednesday at Home of His Daughter Near Reform,” 12 Feb: 04. https://www.newspapers.com/image/1025467838/ : accessed 15 Jan 2025, The Fulton Daily Sun, Fulton, Missouri, online images (newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- “Holland, Thomas C.,” Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/file/10704248/holland-thomas-c-page-41-us-civil-war-service-records-cmsr-confederate-virginia-1861-1865 : accessed 17 Jan 2025), Military Unit: Twenty-eighth Infantry; Full Name: Holland, Thomas C; Age: 21; Year: 1861; Estimated Birth Year: 1839 – 1840; Conflict Period: Civil War (Confederate); Branch: Confederate Army; Served for: Confederate States; Publication Number: M324; Nara Catalog Id: 586957; Nara Catalog Title: Carded Records Showing Military Service of Soldiers Who Fought in Confederate Organizations , compiled; 1903 – 1927, documenting the period 1861 – 1865; Publisher: NARA; Record Group: 109; State: Virginia. ↩︎

- “Elected Brigadier General,” 22 Sep: 01. https://www.newspapers.com/image/1025496084/ : accessed 15 Jan 2025, The Fulton Gazette, Fulton, Missouri, online images (www.newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- “Callawegian Trustee In Confederate Institution,” 22 Nov: 01. https://www.newspapers.com/image/1025503647/ : accessed 15 Nov 2025, The Fulton Gazette, Fulton, Missouri, online images (www.newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- “Count Reveals Heroes of Gray – Veterans of Hard Battles Present at Confederate Reunion,” 02 Oct: 14. https://www.newspapers.com/image/1024712828/ : accessed 15 Jan 2025, The Kansas City Post, Kansas City, Missouri, online images (newspapers.com). $ ↩︎

- 2011. “Legacy: Argument pits states’ rights vs. slavery,” 12 Jun: 13. The Kansas City Star (https://www.newspapers.com/image/821441061/ : accessed 18 Jan 2025). $ ↩︎

Leave a Reply