Mildred Holland (1779-1854)

Today is the 238th anniversary of the birth of Mildred Holland. She was called Milly.

I thought about skipping Milly in my series of birthday posts, and to be honest, I started this a year ago and then just couldn’t bring myself to celebrate her birthday in November 2016. But, remembering the trouble that Ben Affleck and Henry Louis Gates got into by leaving out parts of Ben’s family history in his segment on the PBS series, Finding Your Roots, I decided I had to face Milly and tell her story without skipping anything. Plus, while on vacation in September, I visited the Kingdom of Callaway Historical Society Museum and got a copy of Milly’s probate file. So, I thought I should share some of what I found. It’s difficult to understand how people could live the way they did in Virginia at the time. But, it is documented history, and it is her story.

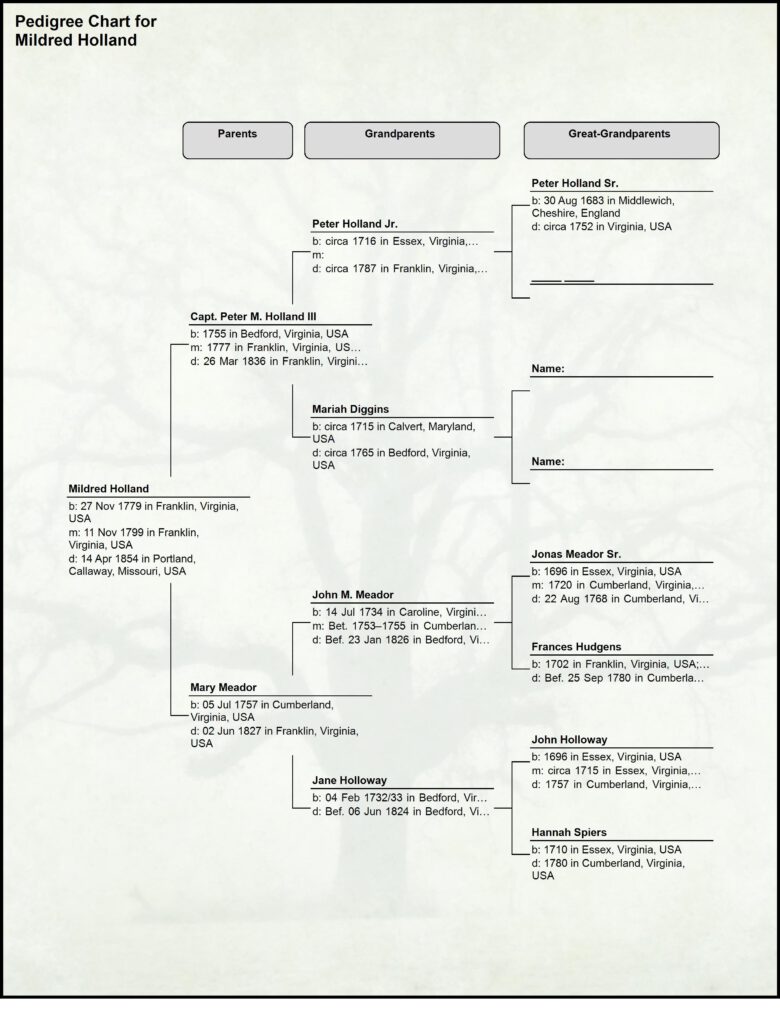

Mildred Holland was born on 27 Nov 1779 in Franklin County, Virginia, in the midst of the American Revolution. She was the child of Peter M Holland and Mary Meador. She had seven siblings, namely: Peter Diggins, Jane, Mary, Sarah Frances, John Meador, Nancy, and Thomas Janson.

Franklin County, where she grew up, is in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountain. It wasn’t formed until she was six years old, so actually, she was born in Bedford County. About the time she was born, residents of Bedford County, living on the south side of the Staunton River, tried to get a new county created. They complained, for example, that they had to travel an unreasonable distance of 30 to 60 miles to the County Courthouse. Others were opposed to the creation of a new county, so the fight went on for years. Finally, in November 1786, they redrew the borders and formed Franklin County out of Bedford and Henry counties.

When she was 19, Milly McCall married William McCall, son of Robert McCall and Elizabeth Aiken, on 11 Nov 1799 in Franklin County, Virginia.

William McCall and Mildred Holland had the following children:

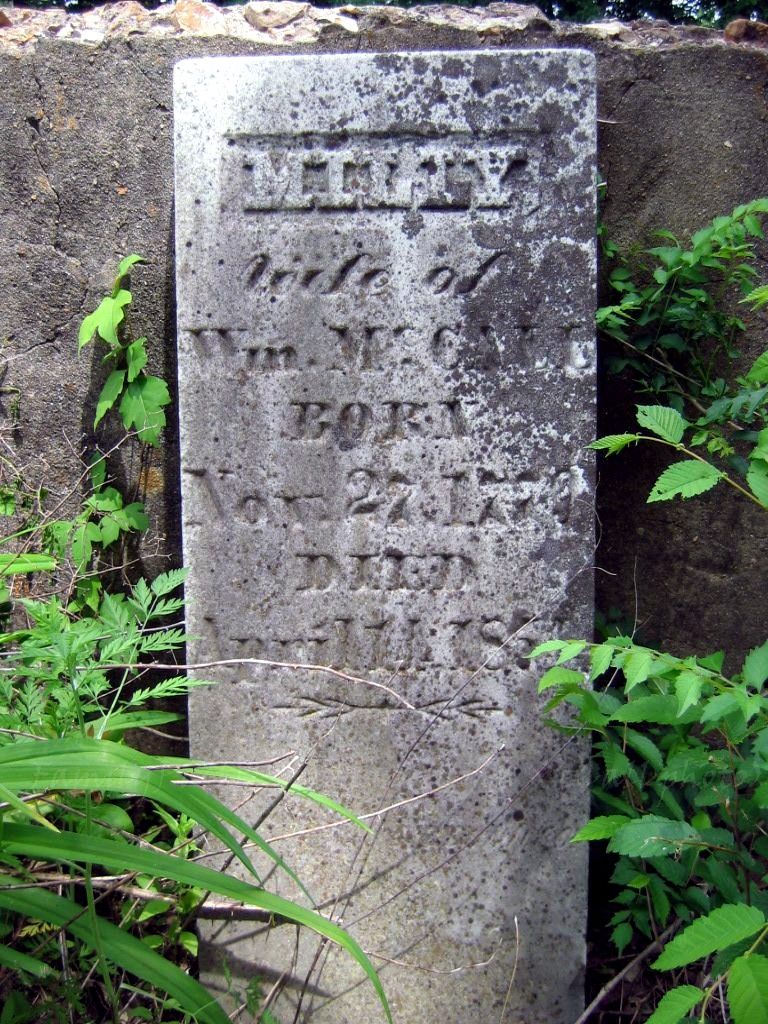

- Peter Holland McCall was born in 1800 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia. He married Zilpha Hodges on 10 Apr 1826 in Franklin, Virginia. He died on 20 Apr 1867 in Reform, Callaway, Missouri, at age 67.

- Lydia McCall was born on 18 Oct 1803 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia. She married Charles Patterson on 02 Apr 1827 in Franklin, Virginia. She died on 18 Sep 1844 in Virginia, at age 40.

- Jane McCall was born between 1801–1810 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia. She married William J. Bell on 19 Feb 1827 in Franklin, Virginia. She died between 1844–1850 in Callaway, Missouri.

- Robert Henry McCall was born on 01 Feb 1806 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia. He married Elizabeth Middleton Gilbert on 05 Nov 1832 in Franklin, Virginia. He died on 22 Jul 1886 in Fulton, Callaway, Missouri,at age 80.

- Mary Lyle McCall was born on 21 Feb 1810 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia. She married Stephen Henry Smith on 24 Nov 1834 in Franklin, Virginia. She died on 26 Jul 1897 in Montgomery, Missouri, at age 87.

- Thomas Fewell McCall was born about 1811 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia. He died between 1842–1 Dec 1844 in Franklin, Virginia.

- William Stokes McCall was born on 02 Dec 1811 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia. He married Martha Jane Smith on 25 Jun 1839 in Franklin, Virginia. He married Sarah Ellen Gregory in Callaway, Missouri. He died on 20 Dec 1873 in Callaway, Missouri, USA (Readsville), at age 62.

- James Elbert McCall was born on 13 Apr 1813 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia. He married Angeline Amelia Gilbert on 07 Nov 1839 in Callaway, Missouri. He died on 24 Dec 1886 in Reform, Callaway, Missouri, at age 73.

- Frances McCall was born on 20 Aug 1815 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia, USA. She married Thomas Kemuel Gilbert on 05 Feb 1838 in Franklin, Virginia. She died on 01 Jul 1872 in Callaway, Missouri, at age 56.

- John Meador McCall was born in 1819 in Glade Hill, Franklin, Virginia. He married Julia Anna Jane Holland on 21 Jan 1849 in Franklin, Virginia. He died in November 1864.

Milly spent most of her life in Franklin County, Virginia. She grew up there on her father’s farm. There are not any records available for Virginia for the 1790 and 1800 Federal censuses, so we can’t glean anything about Milly’s childhood from those records. But, in the 1810 census, her dad owned sixteen slaves, so we can assume that she grew up with slavery seeming normal. After her marriage, she remained in Franklin County, again depending upon slave labor.

Life required hard work in Franklin county. Homes didn’t have running water. Women and children were usually the ones to have to carry water from springs near their homes. “Near” normally being 200 to 500 yards away, often at the bottom of a cliff or steep hill below the house. Large buckets of water had to be lugged up the hill from the spring to the house. The houses that Milly lived in were probably one or two-bedroom log cabins, facing south. Homes had what was called a compass mark on their doors. These marks worked like sun dials so that the women knew when to call folks in for the noon meal.

During butchering season, families preserved meat, but also used the tallow to make candles, and bones and meat scraps in soap making. The tallow candles were one of the only sources of light in the cabins. The fireplace, would have been an important part of the cabin, providing heat, light, and the place to cook meals. Milly may have had a few pewter plates, but there is a good chance that she also used wooden bowls as well as dishes and spoons made from gourds. Basket-making was a specialty of Franklin County. So, Milly probably had her share of baskets made from white oak. Chair bottoms were made using the same process. Flax and cotton were spun into thread and then woven into cloth. Bark and berries were used to dye the cloth different colors. Pelts from bear, deer and raccoons also provided material for clothing. Socks were hand-knit.

In June 1823, when she was 43-years old, Milly was widowed. Her husband, William S. McCall passed away at Gladehill, Franklin, Virginia at the age of 46. Milly’s oldest son, Peter Holland McCall, was an adult at age 23, but her other nine children were minors ranging in age from four to 20. In his will, William provided for this family.

“Wife Milly McCall to have 4 of her choice Negroes for the support of her and the four youngest children, and their Education. Other Negroes, land on south side of Pigg River, Waggon, 3 horses, etc., etc. to be sold and money divided among my children. Sons William S. and Thomas Fewell McCall [Thomas F. McCall not yet of age, Stokes not yet of age.] Two eldest sons not named and any others who are of age to be employed to look after the family business and property as long as they do well and no longer. Wife may lend to each of my daughters a Negro apiece, upon their giving [bond] or their return when ‘Stokes’ comes of age. Milly to receive her 2 choice Negroes, 2 horses, 2 cows, 2 feather beds, furniture, farming utensils [part] likewise the land upon which I now live or else be plentifully supported during her natural life. Even if she marries again, she is to be comfortably provided for. Friend John M. Holland, Executor [John M. Holland declined to serve on August 4, 1823 and Peter Holland qualified].”

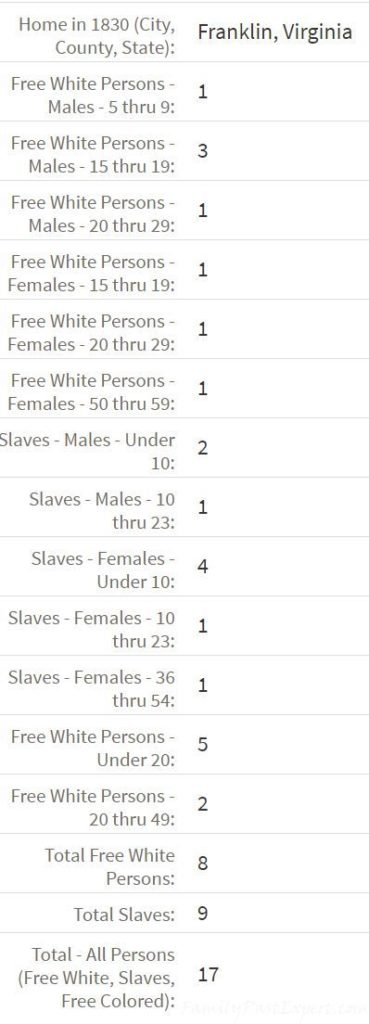

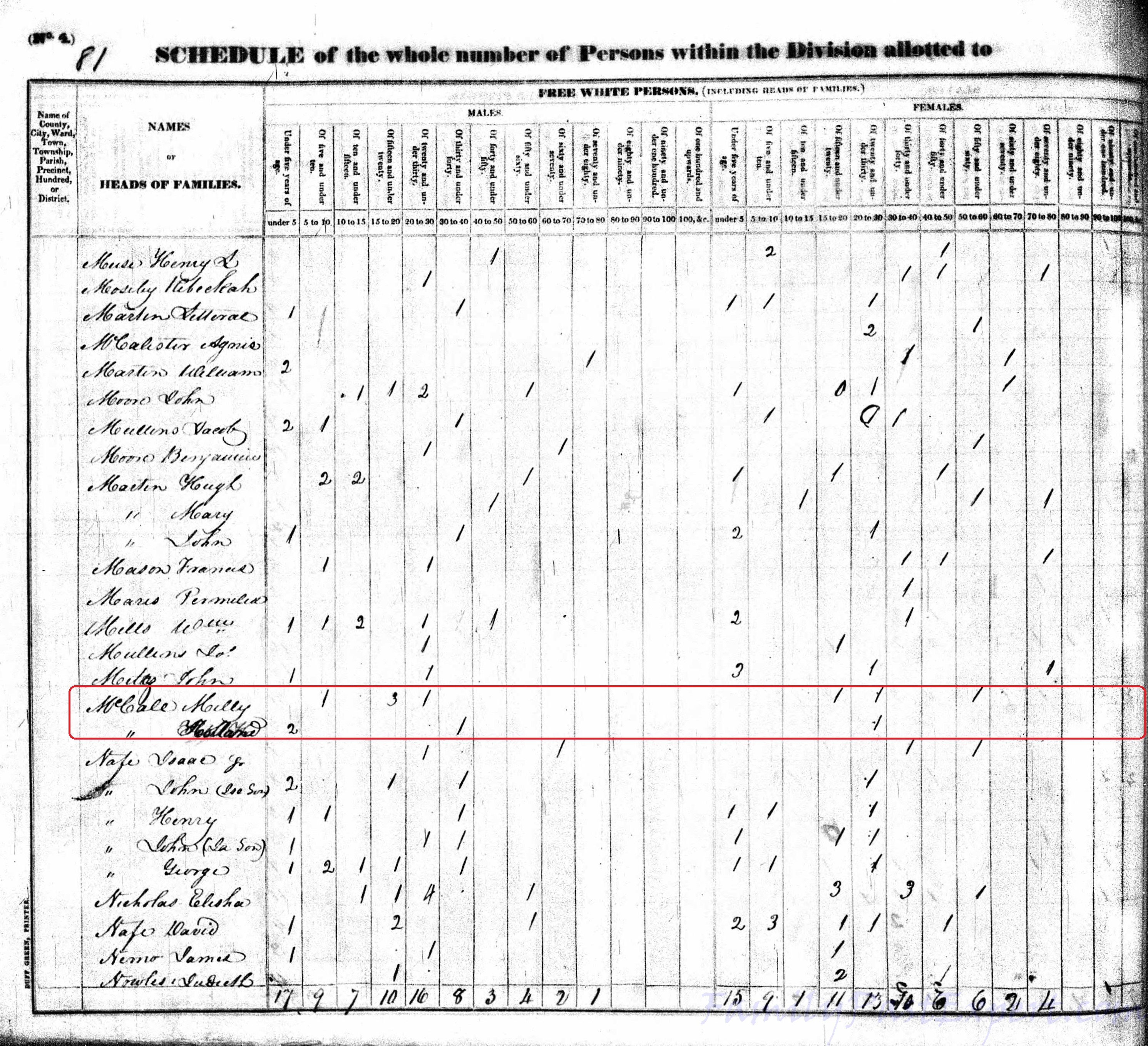

She seems to have been successful in running the plantation as a widow. At the time of the 1820 census, prior to William’s death, the family owned ten slaves. In 1830, seven years after William’s death, she owned nine. In her household, she had eight free white persons and nine slaves. Besides herself, at age 51, were seven of her children.

With the death of her husband, Milly had to worry about more than the household chores. The family kept animals and raised crops. Most of the land in Franklin County is poor for farming. Marshall Wingfield, in his book, Franklin County, Virginia: A History, wrote, “With the exception of the land along rivers and creeks, Franklin County is hilly and stony, and yields discouragingly small harvests in proportion to the labor required to cultivate it. Much of the soil is thin, and when plowed, it washes away in a few years, leaving stones and clay.” In those days, there weren’t fences, so Milly’s hogs and cattle ran around the countryside with hogs and cattle of her neighbors. The hogs ate acorns and chestnuts, and sometimes went wild and never returned home to be fed because they could find so much to eat in the wild.

Milly grew corn and tobacco. Tobacco growing required a lot of labor. Ground had to be prepared early in the year; later seeds were planted; then when plants were six to eight inches high, they had to be transplanted. Then, pests had to be controlled. Hoeing had to be done to keep down weeds, and hornworms had to be picked off plants by hand. In the fall the tobacco had to be harvested by hand and then dried and cured.

Because growing tobacco was so labor intensive, slavery became a popular institution in Franklin County. Wingfield wrote, “The lot of the Negro slave in Franklin was no happier than elsewhere. The same restrictions were imposed.”

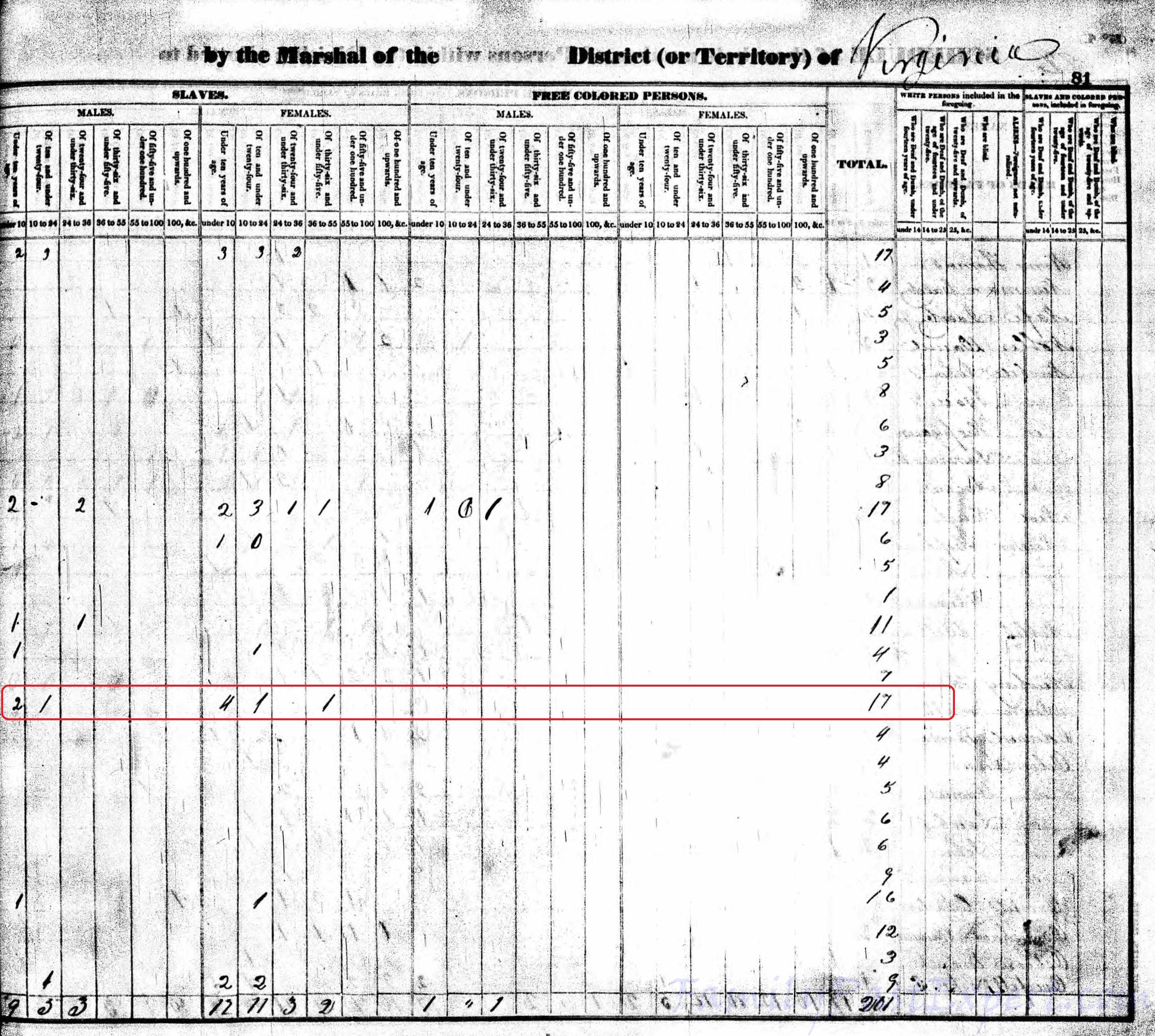

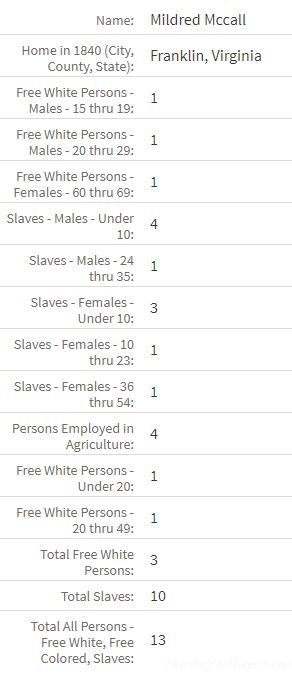

Between 1834 and 1837, seven of Milly’s ten children moved from Virginia to Missouri. Six of them settled in Callaway County. Milly remained in Virginia and kept the plantation running. In 1840, she had ten slaves.

Franklin County was firmly against abolishing slavery. In 1849, years before the Civil War, there was already trouble brewing. The following article from the Richmond Enquirer shows how they really felt about the issue, “…Whereas, the institution of slavery is one peculiar to the slaveholding States, and one with which the North has no right to interfere under the constitution…”

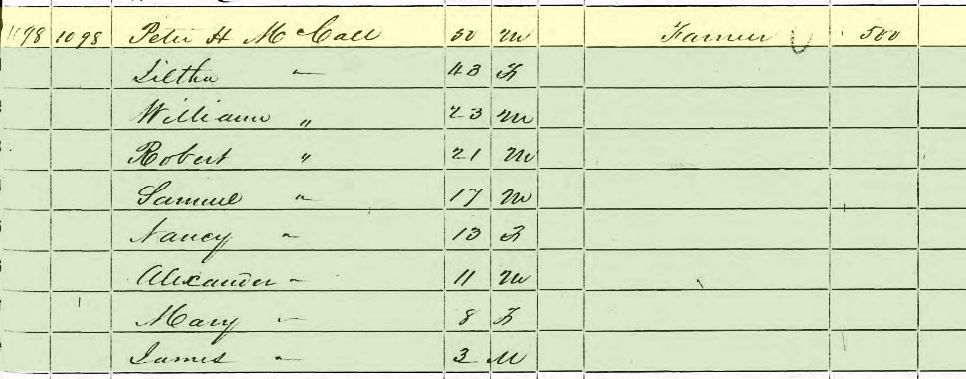

In 1850, Milly was still a slave owner, with several people listed as her property. She had 410-acres of land, though 260-acres of it was unimproved. The farm as valued at $1,500, which would be about $47,600 today using a simple Purchasing Power Calculator.¹ Her youngest son, John Meador McCall, remained in Virginia. He never moved to Missouri with his siblings. In 1850, John was married, but still living in the household of his mother. So, he seems to be the one to have taken over the family farm.

The 1850 Federal Census included a slave schedule that has an entry for each slave. Names weren’t listed, but gender and age were. Unfortunately, Milly’s page is smudged and not entirely readable.

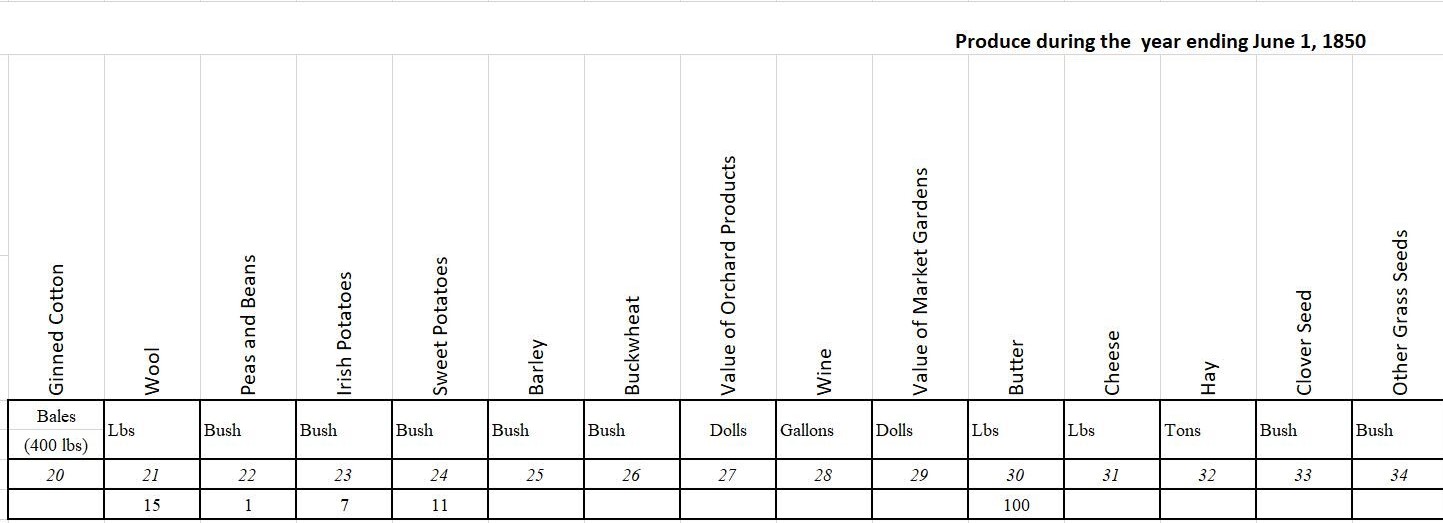

The 1850 Federal Census also included an agricultural schedule. It gives us a glimpse into what Milly was managing on her farm.

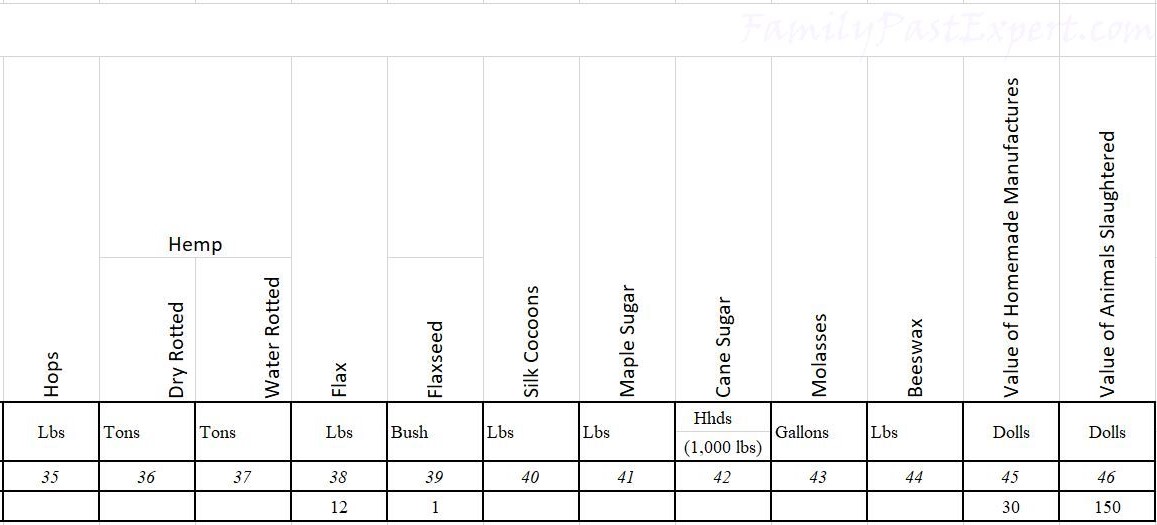

Mildred Holland McCall died while on a visit to Portland, Callaway, Missouri on 14 Apr 1854. She was 74-years old. She was buried in 1854 in the private McCall Cemetery at Readsville, Callaway, Missouri.

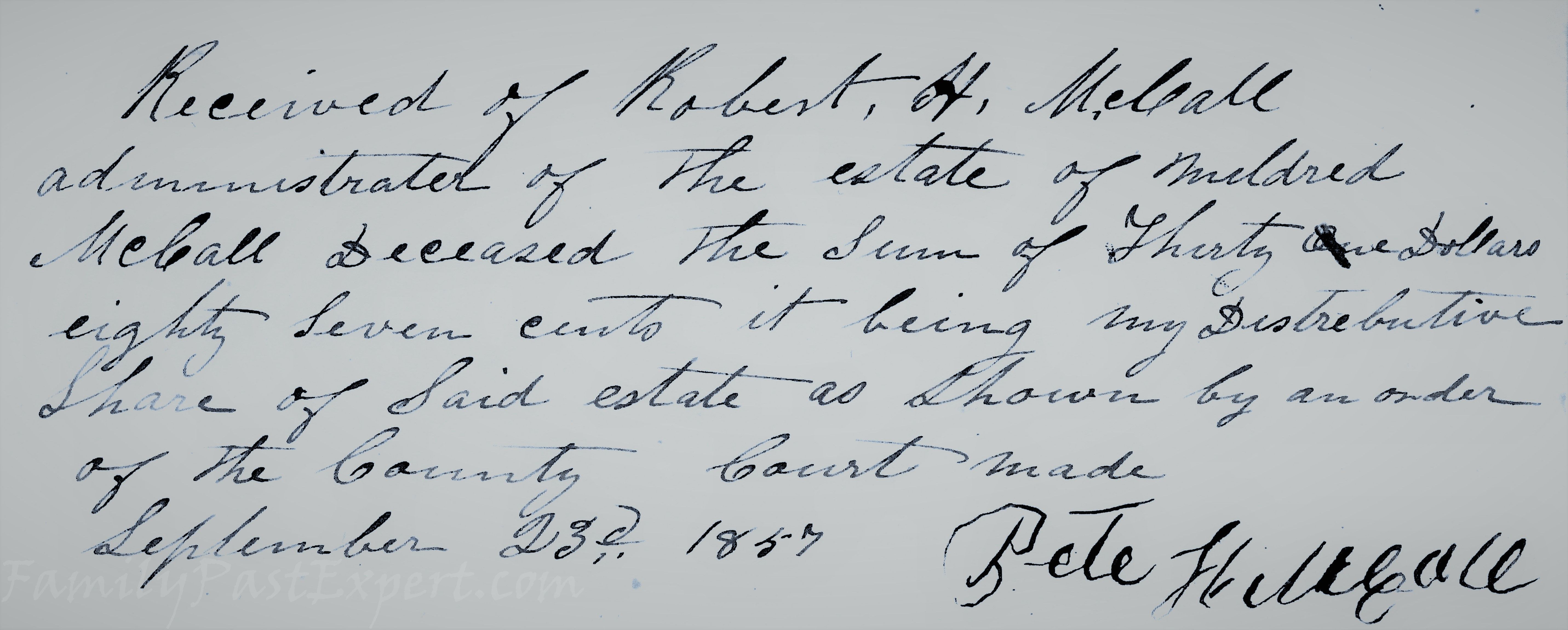

When she died, Milly did not have a will. Her estate was settled in Callaway, Missouri with her second son, Robert Henry McCall, as administrator. It may seem a little odd that the second son, rather than the oldest son, was the administrator. Robert Henry McCall was more well off than his older brother, Peter Holland McCall. In the 1850 Federal census, Peter had real estate valued at $500 and owned no slaves. Robert, on the other hand, had real estate valued at $1,000 and owned nine slaves. There is a family legend saying that Peter was disinherited for marrying a German servant girl. Perhaps there is truth to the story and Peter didn’t get as much help starting out in his adulthood as his siblings? So, maybe Peter didn’t want anything to do with having to be responsible for settling his mother’s estate.

In 1850, Robert owned nine slaves, two were adults and the remainder children. All were black, except for a six-year old boy who was listed as mulatto. It should be noted that Robert wasn’t the only of Milly’s children to have continued the tradition of owning slaves. In 1850, Mary Jane and her husband, William J. Bell owned four; Mary Lyle and her husband Stephen Henry Smith, who lived in Warren County, Missouri, owned eleven; William Stokes owned nine, James Elbert owned three; and Francis and her husband, Thomas Kemuel Gilbert, who still lived in Franklin County, Virginia, had one. It is a mystery as to why Peter didn’t. One might like to think that he was opposed, but it is maybe more likely that he couldn’t afford it.

For whatever reasons, the second son, Robert Henry, was assigned as administrator of his mother’s estate. It took over three years for the estate to be settled.

Milly’s heirs included eight children. Her deceased daughter Lydia’s children were also considered heirs. Son, Thomas Fewell McCall, was also deceased, but did not leave any children, so he was not named.

One of the first orders of business in settling the estate was to take an inventory of Milly’s property. She didn’t own much, but many were common household items:

- one Negro woman

- one bedstead

- one bed and bedding

- one lot of bed clothes

- one coffee mill

- one tea kettle

- one frying pan

- one pot

- one bucket

- $30 cash

The appraised value of her estate totaled $655.50. This record gave the name of her slave as “Letty.” And, though it is now hard to imagine putting a value on a human life, Letty was the most valuable of Milly’s assets.

There were several debts to settle too. For example, the cost of a coffin and headstone for Milly.

In 1855, Robert went about the task of liquidating Milly’s assets. He had to give public notice that he was going to sell a slave that had belonged to Milly.

Next, an estate sale was held. Family members purchasing most of the property for a total price of $31.10. $20.25 was also earned at the sale, for loaning out Letty. The net was $51.35.

By the time the estate was settled, one of the daughters, Jane McCall Bell, had died too. So her share went to her heirs. The exact date of Jane’s death is a bit of a mystery, because she seems to have been alive in April 1854, when her mother died and the probate process began. However, she is not listed in the 1850 Federal Census with her husband and children. So, the census record would lead us to believe that she was deceased prior to 1850. Deaths weren’t recorded in Callaway County back then, so we cannot be sure when she actually died. But, we do know that her share of her mother’s estate went to her heirs.

In the end, son Peter Holland McCall, was not disinherited. Because his mother didn’t have a will, Peter did get his share of what his mother left.

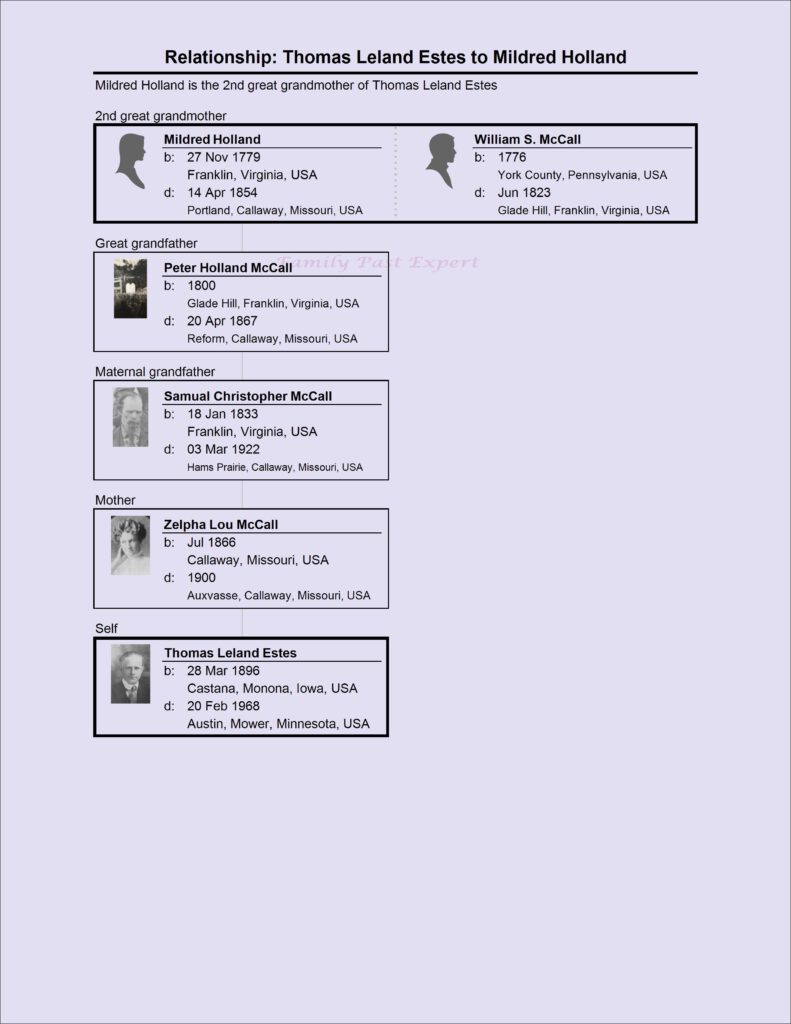

Where is she in the tree?

Notes and Selected Sources:

¹Samuel H. Williamson, “Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to present,” MeasuringWorth, 2017. This answer is obtained by multiplying $1500 by the percentage increase in the CPI from 1850 to 2016.

Ancestry.com. Franklin County, Virginia, Marriage Bond Index, 1786-1858 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 1999. Original data: Wingfield, Marshall. Marriage Bonds of Franklin County, Virginia. Memphis, TN, USA: West Tennessee Historical Society, 1939.

“Franklin County,” Richmond Enquirer, 20 Feb 1849, newpapers.com, 16 Nov 2017, https://www.newspapers.com/image/339035231.

Marshall Wingfield, Franklin County, Virginia: A History, (Baltimore: Clearfield Company, Inc., 1996, 2003) Originally published in Berryville, Virginia, 1964.

Mildred McCall, probate file. Copy obtained from the Kingdom of Callaway Historical Society Museum, Fulton, Missouri, 20 Sep 2017.

William Smith Bryan and Robert Rose, A History of the Pioneer Families of Missouri , (St. Louis: Bryan, Brand & Co., 1876), pp. 354-5, Archive.org (https://archive.org/details/historyofpioneer00bryauoft : accessed 17 Nov 2017).

Leave a Reply