As we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Women’s Suffrage in the United States, this series of posts puts the 19th amendment in context of our own ancestors.

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

19th Amendment

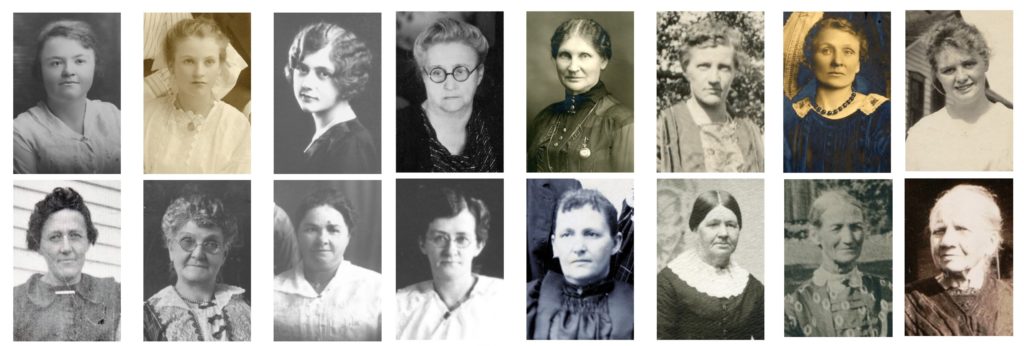

This is the second post in our series on Women’s Suffrage. The first post introduced you to our sixteen female ancestors who were living in the United States in 1920 when the 19th Amendment was signed on 26 Aug 1920.

This post covers efforts leading up to women getting full voter rights.

Some Votes Cast

Prior to 1920, women were allowed to vote.

Sometimes.

Rarely.

Because voting was often tied to property ownership, many states allowed widows with property to vote.

Supposedly, a woman named Lydia Chapin Taft was the first woman to legally vote in the American Colonies in 1756. Her prominent husband had died suddenly and she was allowed to cast a vote at an Uxbridge, Massachusetts, town meeting on whether the town should support the French and Indian war effort. Since her husband had been the largest landholder in the area, they needed her affirmative vote to appropriate funds. So, they let her vote.

Our ancestor Gertrude Lovin Boyce Phillips had ancestors in Uxbridge at this time. Her 2nd great-grandparents Lydia Brown and Edward Hall lived there, and their daughter, Gertrude’s great-grandmother, Betty Hall, was born there in 1768. Lydia and Betty surely weren’t allowed to vote.

From the beginning of European settlement in America, women were almost always kept away from the polling places.

Restrictions for Many

We should note that it wasn’t just women who were denied the right to vote. In early Colonial times, voting was normally restricted to property owners. If you didn’t own property, you couldn’t vote.

By the 1670s, laws were being put in place to do away with indentured servitude and replace the system with permanent slavery for Africans. Laws were put in place to regulate black slaves and restrict free blacks. Both black slaves and free blacks were denied the right to vote.

In 1699 in Virginia and 1718 in Maryland, Catholics were banned from voting. Three other colonies implemented similar restrictions. It was forbidden for Catholic priests to even live in some colonies and Catholics couldn’t be considered freemen in others, so that prevented many Catholics from even settling in those places.

In 1737, New York banned Jews from voting. Three other colonies did the same.

By 1732, all 13 colonies restricted voting to tax payers, landowners, or men who owned a substantial amount of personal property.

The Revolution

A main protest of colonists was that they were taxed without any representation in English Parliament.

Yet, even though a Catholic signed the Declaration of Independence, Catholics, Jews, Quakers, and other were banned from voting. Other white men with property could vote.

Some states, such as New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut allowed Free Black men to vote.

There was always debate on who should vote. Many states changed their rules so that just owning property didn’t allow you to vote – you had to be an actual tax-payer to be eligible to vote. Some states let anyone who had served in the military vote.

Vermont granted universal male suffrage in 1777. They prohibited slavery and indentured servitude and didn’t require a man to own property in order to cast a vote.

Ban Those Women

Though the right for women to vote hadn’t been specifically given in the U.S. Constitution before the 19th amendment, it didn’t prohibit women voting either.

But in the 1770s and 1780s there was a trend to disallow women from voting.

In 1777, women lost the right to vote in New York.

In 1780, women lost the right to vote in Massachusetts.

In 1784, women lost the right to vote in New Hampshire.

In 1787, the U.S. Constitutional Convention gave states the right to decide on voting rights. All states except for New Jersey decided to deny women the right to vote.

This means, for example, that Gertrude Lovin Boyce’s great-grandmothers in New Hampshire and Massachusetts may have been allowed to vote (after the deaths of their husbands) and then had that right stripped away.

After 1787, New Jersey was the only place women had any rights. Between 1776 and 1807, single women owning property worth fifty pounds were allowed to vote in New Jersey.

In 1807, New Jersey revoked women voting rights, limiting voting to free, white males.

Around this time, other tweaks were being made to voting laws too. For example, in 1814, Connecticut changed its definitions and decided that you had to be white to be a freeman. And only a freeman could vote. Rights were stripped from black property owning men.

In 1819, in Maine, the legislature decided that Native Americans who did not pay taxes would no longer be allowed to vote. In 1842, Rhode Island banned members of the Narragansett tribe from voting.

Stricter voting rights were being put in place.

Restrictions Lifting

An often quoted opinion on the connection between property ownership and voting rights comes from Benjamin Franklin.

“Today a man owns a jackass worth fifty dollars and he is entitled to vote; but before the next election the jackass dies. The man in the meantime has become more experienced, his knowledge of the principles of government, and his acquaintance with mankind, are more extensive, and he is therefore better qualified to make a proper selection of rulers — but the jackass is dead and the man cannot vote. Now gentlemen, pray inform me, in whom is the right of suffrage? In the man or in the jackass?”

Benjamin Franklin

By 1790, the property requirements for voting were starting to disappear. None of the new states being admitted to the union had that requirement. Free blacks (men) were allowed to vote in six states.

But, when the first U.S. Naturalization Act passed that same year, only free white people were allowed to gain American citizenship. Asians and other ethnic groups were not allowed to become citizens. Which means they couldn’t vote.

In 1821, Massachusetts and New York dropped the property ownership requirement for voting – unless you were black. If you were a black man, you still had to own property if you wanted to vote.

By 1830, most states had removed their religious voting restrictions as well. These restrictions that had primarily impacted Catholics, Jews, and Quakers, were disappearing.

But, women were still kept away from ballot boxes.

Rights for Some Women, Sometimes

In 1838 in Kentucky and 1861 in Kansas, widows with school-aged children were allowed to vote in school elections.

It wasn’t enough though.

Women started organizing.

In 1848, a woman named Elizabeth Cady Stanton started calling for Rights for Women.

Women Ignored

In 1868, as part of reconstruction, the 14th amendment was ratified. The word male was added to section two of the amendment, essentially denying women the right to vote.

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

14th Amendment, Section 2.

There were a couple exceptions.

Wyoming allowed women to vote in 1869. They even let women serve on juries and hold public office. Decades later when Wyoming sought statehood, Congress fought them on letting women vote. But Wyoming stood fast and Congress relented. It became the first state allowing women to vote when it became a state in 1890.

Utah passed women’s suffrage in 1870 and retained it in 1896 when they became a state.

In 1870, the Federal Government weighed in again passing the 15th Amendment, granting African American men the right to vote, but ignoring women.

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude–

15th Amendment, Section 1.

By the way. Women were not just sitting back and ignoring this. As mentioned earlier, as early as 1848, there were women’s rights conventions and an increasing number of suffragettes. There were failing women’s suffrage votes in many states. There were demonstrations. There were suffrage groups and anti-suffrage groups. There were challenges that made it to the Supreme Court. The men of the Supreme Court, however, ruled against women.

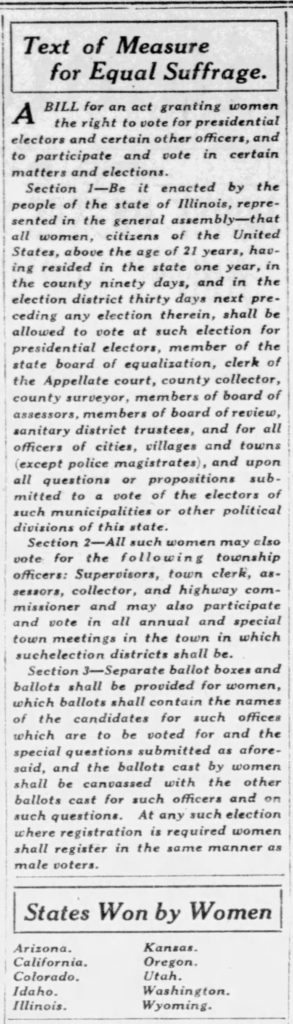

In Illinois, in 1873, women could run for local school offices. In 1891, they were allowed to actually vote for those offices. They got a separate ballot and voting box, but they got to vote. That means that our Amelia Brace, Jane Cornell, and Gertrude Boyce may possibly have voted in school elections.

In 1875, women won the right to vote in Michigan and Minnesota school elections. That means that Barebo Engebretsdtr Torset, who was over 21-years old at the time, may have possibly voted in school elections.

In 1878, a federal amendment to give women the right to vote was introduced for the first time. It took a while before it to be successful. A long while.

Washington and Montana let women vote in the 1880s. Colorado did so in 1893, and Idaho in 1896.

But there continued to be setbacks.

In 1887, Utah women were stripped of their voting rights and the Supreme Court took the rights from women in Washington territory.

At this point, women were losing rights, not gaining them.

However, at the same time, Kansas agreed to let women vote in municipal elections.

And the tide started slowing turning.

Women got to vote…

In 1893 in Colorado.

In 1896 in Utah (their rights being restored).

In 1896 in Idaho.

In 1910, in Washington.

In 1911, in California.

In 1912, in Oregon, Arizona, Kansas, and Alaska Territory.

In 1913, Illinois decided it would be alright for women to vote for president and municipal offices, but not for state or federal legislators. That means that Jane, Amelia, and Gertrude may have cast presidential ballots as early as 1916, in Illinois, and maybe didn’t have to wait for the 1920 election.

In 1914, Nevada and Montana gave women the right to vote.

Why Shouldn’t Women Vote?

Not everyone was embracing women’s suffrage. Things were often violent. Women were injured when a suffrage parade was attacked by a mob. Suffragettes were arrested at gatherings. In 1917, there was a Night of Terror at a workhouse in Virginia. Suffragist prisoners were beaten and abused.

Why were people so threatened by women voting? Note that it wasn’t just men who fought against it.

The National Association OPPOSED to Woman Suffrage published a pamphlet listing many of the arguments.

Votes of Women can accomplish no more than votes of Men. Why waste time, energy and money, without result?

National Association OPPOSED to Women Suffrage.

They encouraged a NO vote on suffrage because:

- 90% of women either do not want it, or do not care.

- It means competition of women with men instead of co-operation.

- 80% of the women eligible to vote are married and can only double or annul their husbands’ votes.

- It can be of no benefit commensurate with the additional expense involved.

- In some States more voting women than voting men will place the Government under petticoat rule.

- It is unwise to risk the good we already have for the evil which may occur.

They had a couple pages in the pamphlet directed specifically at housewives:

- You do not need a ballot to clean out your sink spout. A handful of potash and some boiling water is quicker and cheaper.

- Control of the temper makes a happier home than control of elections.

- Good cooking lessens alcoholic craving quicker than a vote.

- Why vote for pure food laws, when your husband does that, while you can purify your ice-box?

- Common sense and common salt applications stop hemorrhage quicker than ballots.

- Sulpho naphithol and elbow grease drive out bugs quicker than political hot air.

- It provided a list of stain remover tips with a final statement, “There is, however, no method known by which mud-stained reputations may be cleansed after bitter political campaigns.

There were medical reasons to save women for voting too. Some doctors and scientists said that the mental exertion needed for voting, or really any thinking, could harm reproductive health. Others claimed that women had inferior brains. There was also a theory that the human body, especially the female human body, contained a finite amount of energy, so women should save their energy for their reproductive systems rather than for politics and thinking. Furthermore, a pregnant or nursing mother could hurt both herself and the child if she took on the responsibility of voting. Of course, a menstruating woman was in a destabilized condition and could not have the right temperament for politics.

Women continued to fight

The crusade continued on though, with more states recognizing women and granting them the right to vote.

In 1917 in Arkansas agreed to let women vote in primaries, but not the general election. Rhode Island, New York, Oklahoma, and South Dakota granted the right to vote to women.

By 1919, there were 15 states where women had full voting rights, but only two of them were east of the Mississippi River. Those states were:

- Wyoming 1890

- Colorado 1893

- Utah 1896

- Idaho 1896

- Washington 1910

- California 1911

- Arizona 1912

- Kansas 1912

- Oregon 1912

- Montana 1914

- Nevada 1914

- New York 1917

- Michigan 1918

- Oklahoma 1918

- South Dakota 1918

Alaska wasn’t a state yet. But Alaska Territory allowed women to vote.

Many other states didn’t have full voting rights, but did let women vote for president before the 19th Amendment:

- Illinois 1913

- Nebraska 1917

- Ohio 1917

- Indiana 1917

- North Dakota 1917

- Rhode Island 1917

- Iowa 1919

- Maine 1919

- Minnesota 1919

- Missouri 1919

- Tennessee 1919

- Wisconsin 1919

But many states didn’t allow women’s votes until the amendment was finally ratified.

- Vermont

- New Hampshire

- Massachusetts

- Connecticut

- Pennsylvania

- New Jersey

- Delaware

- Maryland

- West Virginia

- Virginia

- North Carolina

- South Carolina

- Georgia

- Alabama

- Florida

- Mississippi

- Louisiana

- Arkansas

- Texas

- New Mexico

- Kentucky

The women did not give up though, and the 19th amendment finally passed. Women across the United States finally got full voting rights in 1920.

The Path to Voting Rights

Finally in 1920, everybody aged 21 and over had full voting rights. No matter the election, you couldn’t be prohibited from voting on basis of sex or race.

But what did out ladies miss? The next two posts will cover elections in which our profiled ladies were not to allowed to vote.

Subsequent posts will include coverage of the 1920 election, a special guest essay on one of our ladies, and discussion of struggles that remain long after 1920.

Selected Sources:

“List of United States presidential candidates,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_United_States_presidential_candidates : accessed 07 Jul 2020).

“Illinois Suffrage Act (1913),” Office of the Illinois Secretary of State (https://www.cyberdriveillinois.com/departments/archives/online_exhibits/100_documents/1913-il-suffarge-act.html : accessed 07 Jul 2020).

Christopher Klein, “The State Where Women Voted Long Before the 19th Amendment,” History, 01 Apr 2019 (https://www.history.com/news/the-state-where-women-voted-long-before-the-19th-amendment : accessed 07 Jul 2020).

“Timeline of women’s suffrage in the United States,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_women%27s_suffrage_in_the_United_States : accessed 07 Jul 2020).

“The Constitution: Amendments 11-27,” National Archives (https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/amendments-11-27 : accessed 07 Jul 2020).

Jewish Women’s Archive. “Pamphlet distributed by the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage,” (https://jwa.org/media/pamphlet-distributed-by-national-association-opposed-to-woman-suffrage : accessed 07 Jul 2020).

“Woman Suffrage Timeline (1840-1920),” National Women’s History Museum (http://www.crusadeforthevote.org/woman-suffrage-timeline-18401920 : accessed 07 Jul 2020).

“Centuries of Citizenship: A Constitutional Timeline,” National Constitution Center (https://constitutioncenter.org/timeline/html/cw08_12159.html : accessed 07 Jul 2020).

“1872 Election Results Grant vs Greeley,” History Central (https://www.historycentral.com/elections/1872.html : accessed 07 Jul 2020).

Scottie Lee Meyers, “Fight for Voting Rights Started With Founding of U.S. Says Author,” -6 Jun 2016, Wisconsin Public Radio (https://www.wpr.org/fight-voting-rights-started-founding-u-s-says-author : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

“Voting Rights Timeline 1605-1917,” (https://votingrights.news21.com/static/interactives/votinghist/timeline.pdf : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

“Lydia Taft,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lydia_Taft : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

“Lydia Chapin Taft – New England’s First Woman Voter,” New England Historical Society (https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/lydia-chapin-taft-new-englands-first-woman-voter/ : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

“From Indentured Servitude to Racial Slavery,” PBS (https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1narr3_txt.html : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

“Maryland,” New Advent (https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09755b.htm : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

“Catholic Church in the Thirteen Colonies,” Wikipedia (Catholic Church in the Thirteen Colonies : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

“History of the Jews in Colonial America,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Colonial_America : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

Marina Koren, “Why Men Thought Women Weren’t Made to Vote,” The Atlantic, 11 Jul 2019 (https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/07/womens-suffrage-nineteenth-amendment-pseudoscience/593710/ : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

Artists’ Suffrage League (1907-c.1918) / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taxation_without_Representation,_Suffrage_Collection.jpg

“Text of Measure for Equal Suffrage,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) 12 Jun 1913, page 2 (https://www.newspapers.com/image/354875762/ : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

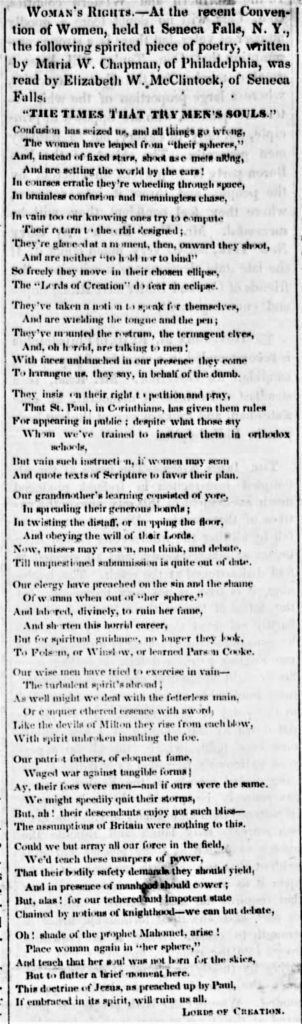

“Woman’s Rights,” Sunbury American (Sunbury, Pennsynvania), 26 Aug 1848, page 1 (https://www.newspapers.com/image/72211442/ : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

Sarah Pruitt, “The Night of Terror: When Suffragists Were Imprisoned and Tortured in 1917,” History, 17 Apr 2019 (https://www.history.com/news/night-terror-brutality-suffragists-19th-amendment : accessed 09 Jul 2020).

Leave a Reply