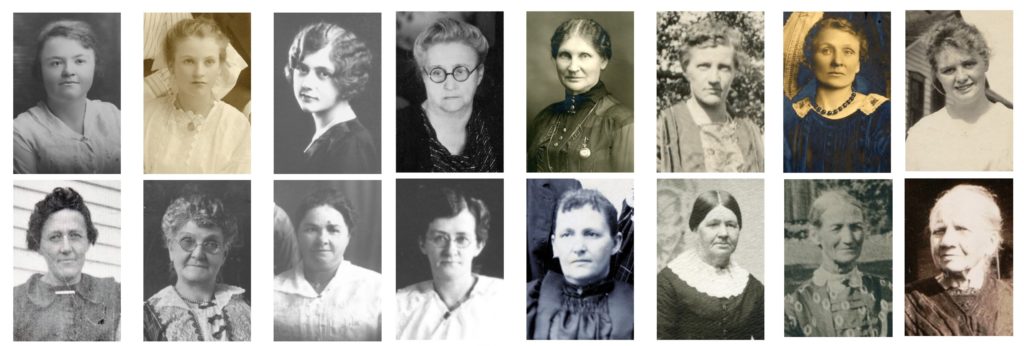

As we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Women’s Suffrage in the United States, this series of posts puts the 19th amendment in context of our own ancestors.

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

19th Amendment

This is the sixth installment of the series on the 19th amendment. Thus far, we’ve learned about the sixteen female ancestors who were alive when the amendment was signed in 1920, reviewed the long road of women’s suffrage, studied the elections from 1868 to 1916, and learned about the situation in 1920. This post takes a long at one of our featured women in more detail.

As a special installment in this series on Women’s Suffrage, we have a guest writer. Coralee has allowed the publication of her essay titled, “Mother’s Legacy.” It describes the special relationship her mother had with the 19th amendment.

– Denise

Mother’s Legacy by Coralee

Life was difficult for Leona. She was the only child of Frank and Mary Miller, living on a farm in DeKalb County Illinois. In the spring of 1915 when Leona was just 15, her mother passed away.

Frank was a wonderful man who played the fiddle at barn dances and was admired by many for his social skills. The young widower encouraged Leona to accompany him so that he’d be unavailable to women who wanted him to drive them home.

Yes, drive. The Millers had a car since the early 1900s, although Leona and a neighbor boy took a horse and buggy to the high school, which was five miles south of the farm. Sandwich, 60 miles southwest of Chicago, was established in 1859 (City History n.d.).

Telephones came to the community in 1898, electricity in 1893 (City History n.d.). Frank even installed an indoor bathroom. As an 1892 graduate of Sugar Grove High School, he briefly attended business school. It seemed he preferred modern technology over tilling the soil of the 200-acre farm that his wife inherited as the youngest in a family of 14.

Most farm girls in that area were married by 18 years old, but not Leona. Neighboring farmers who came from the same family expected her and their young man, Sport Stahl, to marry. That would lead to a monopoly of acreage in two bordering townships.

However, Leona felt they had little but farming in common. She loved reading and socializing with high-school friends, areas that did not appeal to Sport. Perhaps another stumbling block was Leona’s sense of humor that her math teacher described as “overdeveloped.”

The local newspaper, the Sandwich Free Press, published the following story:

“Many good times have been enjoyed by the classmates of Miss Leona Miller at her home north of town and last Wednesday evening was no exception. Two bob loads of the seniors drove out there and indulged in dancing and games, and Miss Leona, assisted by some of the girls, served a most appetizing luncheon. Mr. Miller acts as host and very materially adds to the enjoyment of the evening. The only regret is that as this is their senior year the class fears these good times are almost over.”

(Sandwich Free Press 1918)

But another article proved otherwise:

“On Saturday night, December 28, 1918, the seniors of the class of 1918, motored out to Leona Miller’s for a class reunion. They have had several parties there, but this was pronounced the most successful of all. Following the amusements of the evening, Miss Miller served refreshments, after which they all departed homeward, declaring they would call again some evening.”

(Sandwich Free Press 1919)

Leona started a diary in her teens. Her entries were brief. Eight consecutive entries included: Pa went to town; Pa went up to the school house and fixed the pipe in the morning; Pa butchered the calf; Pa and ma went to the Farmer’s Club; Pa and I went to town in the afternoon; We went to Grandma’s; Pa got caught in the corn slicer; Pa and ma washed.

After Mary died, Leona and Frank continued to stay busy, sharing household and farming duties. Meanwhile, discussions about women being allowed to vote began to surface. The timing was right for the father/daughter team.

It was the 19th amendment, also known as the “Anthony Amendment” after Susan B. Anthony. As early as 1878 she had influenced Senator Aaron Sargent of California to introduce such a bill. But several attempts to pass a women’s suffrage amendment failed—until 1919.

Arguments against women voting were strong. They would simply vote for the candidate their husbands supported, some said. Besides, their place was in the home, not politics.

Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin all made a mad dash to be first. According to the National Park Service, Illinois had to redo its vote a week later after discovering the document read “all events and purposes” rather than “all intents and purposes.” (19th Amendment By State 2019) (Illinois and the 19th Amendment 2019) (McClelland 2019)

Sources differ on which was first. The three states show approval on June 10, 1919 with Illinois clocking in at 10:48 a.m. and Michigan four minutes later. However, Michigan claimed that Illinois’ wording caused a delay of seven days.

It was noted that appearing before the Secretary of State in Washington, D.C. was the official ratification. Michigan beat Illinois by 1½ hours. Not so, claimed Illinois.

Illinois governor Lowden telegraphed the Secretary of State at Washington to send in at once a corrected certified copy of the resolution. Illinois researchers said Illinois was entitled to be named first.

The Chicago Tribune reported on June 11, 1919 that Illinois was the first state to ratify the women’s suffrage amendment to the Constitution. (Phillips 1919) The amendment read: “The right of citizens of the United States shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” (19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution 2016)

The controversy has never ended. Nevertheless, a site recognizing ratification lists this order: Illinois – June 10, 1919, Michigan – June 10, 1919 and Wisconsin – June 10, 1919.

Of the 48 states, 36 needed to ratify in order for the amendment to pass. On Aug. 18, 1920, Tennessee made it happen. After an amendment is ratified, it requires certification by a government official. (19th Amendment By State 2019)

The New York Times carried the story about the signing. On Aug. 26, United States Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby signed a proclamation behind closed doors at 8 a.m. in his own house in Washington, D.C. (Colby Proclaims Woman Suffrage: Signs Certificate of Ratification at His Home Without Women Witnesses 1920)

The significance of Aug. 26 brings us back to Leona. It was her 21st birthday.

The next step was getting women to register. An Oct. 14 Free Press article stated, “Women should be registered under their own name, and not that of their husbands: Mary Smith, and not Mrs. John Smith.” (Sandwich Free Press 1920)

As to the sentiment concerning the election, there was immense dissatisfaction over Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s administration. The election was dominated by the American social and political environment in the aftermath of World War I. The wartime economic boom had collapsed, and the country was deep in a recession. (End Wilson “Dynasty,” Plea of Senator Lodge to G.O.P. Natonal Convention 1920)

At home the year 1919 was marked by major strikes in the meatpacking and steel industries and large-scale race riots in Chicago and other cities. (75,000 Strike In Local Area; Million Loss? 1919) (Troops Act; Halt Rioting 1919)

Election Day was Nov. 2. The early morning hours were not the best for out of doors work. It snowed, it rained, and then snowed some more. After dinner the sun came out.

The headline in the Nov. 4 Free Press read: HARDING AND COOLIDGE WIN IN LANDSLIDE. Voting may not have been by secret ballot as is suggested by the same newspaper. “The gentler sex merely added to the huge Republican plurality” and “The women, like their husbands, brothers and sons were determined to have a change of administration” (Sandwich Free Press 1920)

The paper also revealed that “one man voted Republican while his wife went and cast a Democratic vote.”

Leona, too, voted Republican. Being able to be part of this momentous occasion was something she talked about for many years to come.

Time passed, and a few years later Leona met Floyd Phillips at a dance. He was a World War I veteran who graduated from the high school in Sugar Grove, only 12 miles from Sandwich. In the early 1920s Floyd and his four brothers spent summers farming in Fannystelle, Canada. But he and Leona spent time together whenever he returned home.

Leona related that Floyd didn’t seem to be in a hurry to get married, so she started dating a neighborhood man. When Floyd found out, he was upset saying, “I thought we had an understanding.” She responded, “That’s news to me.” He immediately proposed to her.

Frank passed away unexpectedly on March 16, 1925 at the age of 51. His obituary described him as a “devoted father,” and Leona as a “devoted companion.” Grandmother, Jane Miller, came to the farm to live with her.

Floyd returned from Canada to manage the farm, and the couple married on April 17 when Leona was 25. They had a stillborn son, Harold, and three other children: Stuart, Lowell and Coralee.

Following 46 faithful years together, Floyd passed away on July 7, 1971. Probably the most unlikely time for Leona’s overdeveloped sense of humor to come into play was during the planning of his funeral. A family member was trying to think of the word “eulogy,” but it simply wouldn’t come to mind.

“What do you call something where you talk about a person whether they’re living or dead?” he asked. “A bridge club,” Leona responded.

Although she had many hardships, she was grateful for what she had, not bitter about what had been taken away. She was that way until the very end.

The last two years of her life she was in and out of nursing homes and the hospital with intermediate stays at home. Five months before she died, it was determined she had a rare form of cancer.

For the most part Leona was kept pleasantly occupied during her illness. She had a steady parade of visitors, and she loved to read everything she could get her hands on. But one day she found herself lying in bed feeling sorry for herself. That would never do.

The previous week’s newspapers reported Betty Ford’s mastectomy. She decided the first lady must be feeling blue, so she wrote her a letter. Then she wrote another letter, that one to the daughter of her son’s friend. Julie was 19 years old and intellectually disabled. Leona decided she probably didn’t receive much mail.

Her next project was to place an order through a magazine that featured inexpensive and unusual gifts. Since her son-in-law was currently growing a new mustache, she tucked a couple of dollars inside an envelope and bought him a mustache comb. While she was at it, she decided to order something for herself. For years she had admired crystal bells, and one in the catalog caught her eye.

“Why not?” she asked herself. “I don’t know what I’m saving my money for. The rainy day is here!”

Leona passed away on Feb. 11, 1976.

Her time on this earth encompassed advances in technology, extensive travels throughout the United States and historic events.

She embraced all of it.

Suffrage

Our seventh and final installment in this series will take a look at how the 19th amendment was maybe just a first step in women’s rights. The quest for equality continues.

Works Cited

2019. “19th Amendment By State.” National Park Service. July 8. Accessed September 10, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/womenshistory/19th-amendment-by-state.htm.

2016. “19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.” America’s Historical Documents. September 08. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/19th-amendment.

Chicago Daily Tribune. 1920. “End Wilson “Dynasty,” Plea of Senator Lodge to G.O.P. Natonal Convention.” June 09: 6. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.newspapers.com/image/355017533.

n.d. “City History.” Sandwich Illinois. Accessed September 9, 2019. http://www.sandwich.il.us/city-history.html.

2019. “Illinois and the 19th Amendment.” National Park Service. August 9. Accessed September 10, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/articles/illinois-and-the-19th-amendment.htm.

McClelland, Edward. 2019. “100 Years Ago, Illinois Was First to Ratify National Women’s Suffrage.” Chicago Magazine. June 10. Accessed September 20, 2019. http://www.chicagomag.com/city-life/June-2019/100-Years-Ago-Illinois-Became-the-First-State-to-Ratify-Womens-Suffrage/.

Phillips, E.O. 1919. “Women’s Vote is Ratified by Three States.” The Chicago Daily Tribune, June 11: 1-2. Accessed September 20, 2019. https://www.newspapers.com/image/355041166.

Sandwich Free Press. 1918.

Sandwich Free Press. 1919. January 01.Sandwich Free Press. 1920. October 14.

Sandwich Free Press. 1920. November 04: 1.

The Chicago Daily Tribune. 1919. “75,000 Strike In Local Area; Million Loss?” September 23: 1-2. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.newspapers.com/image/355178895.

The Chicago Daily Tribune. 1919. “Troops Act; Halt Rioting.” July 1919: 1. https://www.newspapers.com/image/354949716/.

The New York Times. 1920. “Colby Proclaims Woman Suffrage: Signs Certificate of Ratification at His Home Without Women Witnesses.” August 27: 1, 3. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.newspapers.com/image/26760769.